In the tumult of midterm season (which is to say, anytime after the second week of classes) Penn students need motivation. What better way to fuel a study session or shift at work than with music pointing toward the ultimate end goal? According to some, it’s not love—Valentine’s Day is over. Not altruism either: “Changing the world” is much harder than your college admissions essays might’ve assumed. The answer is cold, hard cash—but not according to all of these tracks, which provide a variety of outlooks. All that glitters is not gold, but these songs sure are.

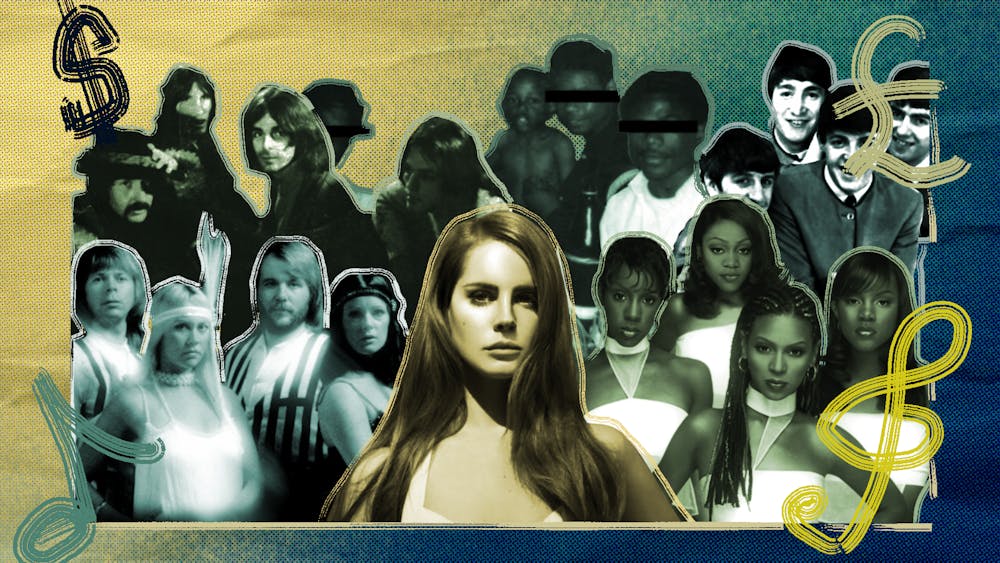

“Money” — Pink Floyd

One of many songs to proudly inherit from your dad’s music taste, “Money” starts with a unique intro: literally, the sound of money. After the distinctive sound of an old cash register, follows a splicing of noises, including the clink of shiny coins and the tearing of paper. They make up a seven–part loop that gradually melts into one of the best basslines in ‘70s rock. Then the song’s lyrics come in, satirizing the lifestyles of the obscenely rich. “I’m in the high–fidelity first–class traveling section / And I think I need a Lear jet,” David Gilmour sings. The best line, though, might come near the end: “Money / So they say / Is the root of all evil today,” it declares. “But if you ask for a rise / It’s no surprise that they’re giving none away.” In true Pink Floyd fashion, add in about three minutes of instrumental—saxophone and guitar solos delivered by Dick Parry and Gilmour, respectively—and you’ve got yourself a classic.

“Money Trees” — Kendrick Lamar, Jay Rock

We encounter another iconic loop in Kendrick Lamar’s 2012 hit “Money Trees,” with one of the most creative uses of a sample you’ll ever hear. The otherworldly instrumentation that repeats throughout the track is a snippet of alternative band Beach House’s "Silver Soul." Producer DJ Dahi reversed the sample and added drums to it to create a stellar motif that repeats throughout the track. In terms of the song’s storyline, though, “Money Trees” couldn’t be more different from “Money.” In contrast to the nameless one–percenter protagonist in Pink Floyd’s lyrics, Lamar raps about growing up in poverty in Compton, Calif. He discusses “dreams of living life like rappers do,” even while tempted by the temporary payout—emotional and financial—of sex, drugs, and crime. Economic stability is elusive, gang violence abounds, and the phrase “ya bish” is all too catchy. Money might not grow on trees, but young Kendrick was determined to plant his own and turn his circumstances around. “Money trees is the perfect place for shade,” Lamar sings, “And that’s just how I feel.”

“Can’t Buy Me Love” — The Beatles

Ah, The Beatles, with their mop–top bowl cuts, awkward grins, and starstruck crowds of fangirls. "Can't Buy Me Love" is a short but sweet tune off their 1964 album A Hard Day’s Night, combining catchy choruses with punchy drums and guitar. For a band aimed at worldwide success, Paul, John, George, and Ringo express a surprising detachment from material riches. With the realization that you can’t purchase a relationship at the local five and dime, cash becomes extremely expendable: “I’ll buy you a diamond ring my friend / If it makes you feel alright.” It’s easy to understand the track’s romantic appeal, as it places love above all else; “I may not have a lot to give / But what I got, I’ll give to you,” Paul McCartney sings. (Later on, looking back on The Beatles’ vacation in Miami after their first American tour, he would joke, “It should have been ‘[Money] Can Buy Me Love,’ actually.”) Regardless, once you know the words, it’s a song that bounces around your head for hours … and you’re not upset about it.

“Money, Money, Money” — ABBA

“Money, Money, Money” is ABBA's contemplation on the merits of becoming a trophy wife. What else is a girl expected to do in “a rich man’s world”? The piano and synthesizer that dominate the sound create a sense of drama, and the song is as much a relatable rant as it is the pinnacle of disco pop. Any college student can empathize with working hard, paying the bills, and in the end, as Anni–Frid Lyngstad sings, feeling “there never seems to be / A single penny left for me” (first years, if this doesn’t strike a chord yet, just wait). Taking into account that it wasn’t until 1974, just two years before this song’s release, that women in the United States gained the right to open a bank account on their own, “Money, Money, Money” is more than just a would–be gold digger’s anthem. “Ain’t it sad?”

“Bills, Bills, Bills” — Destiny’s Child

ABBA’s debate on rags and riches finds a determined and sassy answer, courtesy of legendary girl group Destiny’s Child. On "Bills, Bills, Bills," we listen to the tale of a woman whose boyfriend is a bit too comfortable after the honeymoon phase at the start of their relationship and is starting to take far more than he gives. He’s proving he’s “a scrub … / who don’t know what a man’s about.” What are they saying a man’s about? Earning money, or at the very least being dependable. The lush vocal harmonies that abound on the track—especially on the “so” in “so, you and me are through”—are so good we’re convinced the girlfriend means business. And of course, the snappy lyricism hits its peak with a great pun: “Can you pay my bills? / Can you pay my telephone bills? / Do you pay my automo’ bills?” If the answers to these questions are no … Destiny’s Child has bad news for your romance, and good news for your wallet.

“Million Dollar Man” — Lana Del Rey

Finally, we have the tenth track on Lana Del Rey’s debut major–label album, Born to Die—a grandiose ode to a “Million Dollar Man.” The song is relatively slow in terms of tempo, but Del Rey’s low vocals, matched with jazzy piano and sweeping violin, build to a chorus that’s as heartwrenching as it is cinematic, especially near the three–minute mark. The lyrics describe a relationship that, on the surface, seems glamorous and easily lives up to the standards we received from Destiny’s Child. Del Rey is with this man for two main reasons. In a reference to Elvis Presley’s cover of “Blue Suede Shoes,” it’s ”one for the money / and two for the show”—which is to say, for his wealth and for the thrill. But the man she describes is “dangerous, tainted and flawed.” “You’ve got the world, but baby, at what price?” she asks, suggesting that money isn’t everything. As nice as it is to have a stuffed wallet and a lover who “look[s] like a million dollar man,” Del Rey teaches us there are other, more devastating ways to be bankrupt. The master of double–meanings still sings, “Why is my heart broke?”