The cinematic era defined by superhero films has come to an anticlimactic close. Marvel movies are flopping and copycat rivals are failing even worse. Computer–generated imagery should have been a godsend for sci–fi. Without the constraint of reality, filmmakers can construct natural worlds not in nature, crowds without extras, and aliens without janky prosthetics. Instead, the useful artistic tool has become a crutch, and audiences are over it. Dune is the answer. In Dune: Part Two, director Denis Villeneuve and his elite team combine techniques of modern and classic filmmaking for a sequel so epic that most current blockbusters look amateurish in comparison. This masterpiece of an adaptation turns the second half of Frank Herbert's Dune into a cinematic event akin to The Lord of the Rings trilogy.

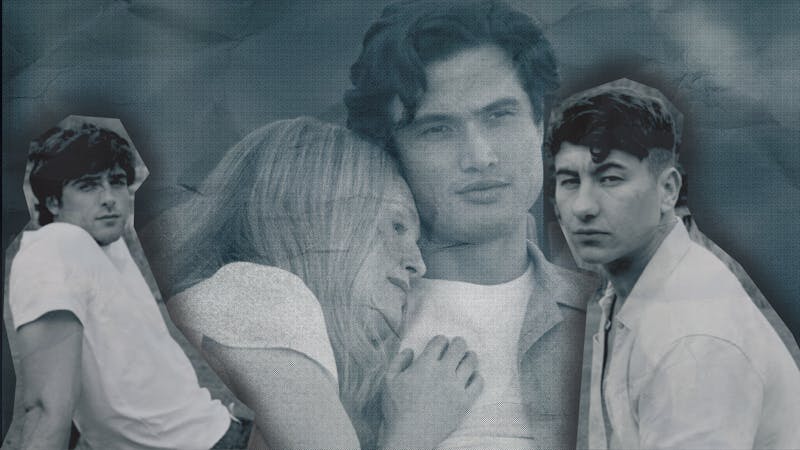

Dune: Part Two unfolds a tragic romance between Paul Atreides (Timothée Chalamet) and Chani (Zendaya). Paul must choose between his love for Chani, and, by extension, her Fremen people, or the inevitable drive for power and revenge, leading him to become the messianic figure foretold by prophecy. The cast of Dune: Part Two features some of the most talented names in Hollywood. Austin Butler's wildly entertaining portrayal of the sadistic Feyd–Rautha and Rebecca Ferguson's villainous Lady Jessica are among the film's standout performances. Dune: Part Two asks the most of Chalamet, and he delivers. By the cliffhanger ending, he commands the screen as a leader, inspiring his followers and terrifying his enemies.

The other stars of the show are off camera: composer Hans Zimmer and cinematographer Greig Fraser, who both won Oscars for the first Dune film. Zimmer’s love theme narrates Paul and Chani’s relationship, and Fraser displays a stellar integration of CGI. Fraser excels at lighting the film's frequent action scenes, such as a black–and–white arena fight shot in infrared and a final duel illuminated by the setting sun of Arrakis. In a movie about faith, the look of Dune is almost a religious experience. Despite the spectacle, Villeneuve keeps the focus on his characters. We see Paul’s journey to messiah through the reactions of those closest to him: Chani and his mentor Stilgar (Javier Bardem). Additionally, the camera shoots Paul differently as the film progresses, incorporating more low angle and profile shots. The Dune universe succeeds from the scales of intimate gestures to thousand–foot sandworms.

If Dune: Part Two functions as a work of art rather than a Marvel “theme park,” it should have themes and ideas to analyze. Here, the film falls somewhat short. The adaptation of Dune reduces some of the more controversial messages of the book, particularly those related to psychedelics and Islam. The Fremen are mostly de–Islamized, a safe choice made to avoid cultural stereotypes and to broaden the audience. However, this limits the intended political implications of a story whose heroes are guerrillas fighting a religious war against technologically advanced imperialists. The main theme now focuses on the potential dangers of messiahs and outside saviors, with many calling it a critique of white savior stories.

In reality, Dune: Part Two represents a most specific variation of the white savior trope, where a white man leads a non–white group in their fight to freedom. Other prominent cinematic versions of this trope are Dances with Wolves (1990), The Last Samurai (2003), and Avatar (2009). Dune: Part Two tries to subvert the trope of these movies by asking the question: “What if a white savior was evil?”

But, this doesn't challenge the core of the unrealistic white savior narrative. The trope serves as a narrative device to teach audiences about a foreign culture through the digestible presence of a white character. Second, white saviorism fulfills the fantasy of a presumed white audience where one joins an oppressed culture to lead a freedom struggle while retaining the benefits of whiteness. Dune adheres closely to these archetypes, neglecting its subversive intent.

A major influence on Herbert's book was Lawrence of Arabia (1962), the prototypical example of a white savior leader. Both stories center on white outsiders who unite a Bedouin people in an anti–imperial guerrilla rebellion, which they are tragically destined to betray. To the credit of these films, they recognize a dilemma inherent to white saviorism: The outsider, as leader, stays separate from the people and acts with different interests to theirs. This idea is the core conflict of both films. They emphasize the evils of imperialism and justify struggles for freedom. However, in doing so, they make native populations appear stupid, acting against their own interests by blindly following a treacherous outsider. Sadly, what may have been a more progressive story in 1962 no longer reads that way in 2024.

Dune: Part Two works best on its pristine surface, built around a series of set pieces each more exciting than the last. The final quarter of the film is as exhilarating a theatrical experience as possible to date. In fact, do not take a date to see Dune: Part Two. You will spend the entire two hours and 46 minutes wholly focused on the screen, until you're standing on your seat as the credits roll, pledging allegiance to the Lisan al-Gaib and his galactic holy war.