To the untrained eye, 4B looks like the next shiny feminist export: edgy, viral, and ready to be hashtagged into empowerment. In the United States, where girlboss feminism still clings to its dying breath, the 4B movement has been flattened into a palatable rejection of men and motherhood, a rebellious lifestyle brand made for Instagram captions.

But 4B isn’t a revolution; it’s a resignation. It’s the reluctant acknowledgement that in Hell Joseon—the satirical term for the unlivable, unforgiving hellscape that is modern South Korea—love, family, and ambition are mutually exclusive luxuries. And for most women, they’ve never been on the menu.

Western feminists have adopted the rhetoric of 4B without understanding it, the same way they once latched onto the Orientalist concept of “han,” Korea’s so–called “national sorrow,” to add a touch of exotic pain to their thinkpieces. In truth, han was weaponized by Imperial Japan and parroted by the Park Chung Hee regime, designed to keep Koreans enduring, silent, and compliant. Now, 4B is undergoing the same erasure, reduced to a hollow statement of empowerment by women who have never had to choose between raising a family and preserving their dignity. 4B isn’t a feminist dream; it’s the nightmare you can’t wake up from, rebranded for an audience too detached to notice.

Hell Joseon is not a place but a concept—a bitter metaphor Koreans use to describe the beautiful, unlivable machine their country has become. The word Joseon harks back to Korea’s last dynasty, a 500–year reign often romanticized for its Confucian values and cultural achievements but equally marked by hierarchy, rigid social roles, and suffering disguised as duty. To invoke Joseon in this modern context is to say that despite all the skyscrapers and K–pop idols, the soul–crushing constraints of the past never really disappeared; they simply got a facelift.

In the United States, the word “feminist” is in the mainstream. It carries some respectability and even marketability. But in Korea, it’s closer to a curse, whispered with disdain or wielded as a weapon. Women who align with feminist ideals or movements like 4B face severe backlash: online harassment, workplace discrimination, and social ostracism. This cultural stigma makes the Western celebration of 4B as a trendy, feminist statement feel painfully naive. The United States lacks Korea’s entrenched hostility toward feminism, making it easier to romanticize 4B as empowerment without reckoning with the risks its adherents face.

Corporate culture demands loyalty at the expense of everything else: health, time, even identity. Workdays stretch endlessly into evenings filled with mandatory drinking sessions, where workers are expected to down soju with bosses and smile through their exhaustion. Men, after enduring military conscription that leaves them bruised in body and spirit, are expected to return as breadwinners. Women, even if they’ve climbed the same ladder, are expected to step aside, marry, and dedicate their lives to unpaid domestic labor.

And when there’s nowhere left to run, the machine still finds a way to squeeze. Korea has the highest suicide rate of any OECD country—a grim indicator of just how many people decide that death is the only escape. These are not isolated tragedies but systemic failures, as much a product of the nation’s structures as its glittering skyscrapers.

Hell Joseon may feel like a uniquely Korean tragedy, but its architecture bears the fingerprints of foreign hands. The United States loves to admire Korea’s resilience, marveling at its rapid industrialization while glossing over the cost. What it doesn’t acknowledge is how its own legacy helped lay the foundation for the misery it now pretends to pity.

During the Korean War, the American military didn’t just bring soldiers—it brought systems of exploitation. Camptowns (gijichon) erupted around U.S. bases, turning Korean women into commodities to satisfy foreign troops. These weren’t centers of empowerment; they were industrial complexes of despair, their foundations echoing the atrocities of Japanese “comfort women” camps. For the women trapped in them, there was no choice, only survival. And when the war ended, these systems of abuse were swept under the rug—another compromise for a country desperate to rebuild at any cost.

The United States speaks of solidarity with Korean feminist struggles, but its role in perpetuating those struggles remains unspoken. It celebrates sex work as empowerment while ignoring how it systemically imposed that labor on marginalized women in Korea. It lifts up movements like 4B without acknowledging how its own policies exacerbated the conditions those movements are fighting against. Western feminism, with its glossy slogans and commodified narratives, doesn’t know what to do with the parts of history it helped create. It simply looks away.

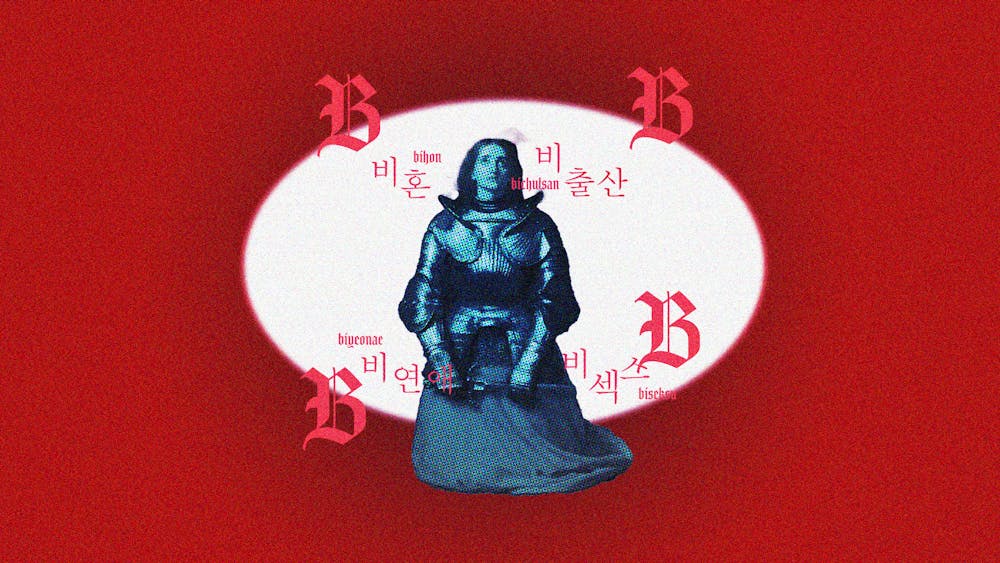

The 4B movement—short for the rejection of biyeonae (dating), bisekseu (sex), bihon (marriage), and bichulsan (childbirth)—is not a war cry but a white flag. It’s a feminist response born from the constraints of Hell Joseon, where the idea of “having it all” feels like a cruel joke rather than a genuine choice. For Korean women, 4B isn’t about hating men; it’s about rejecting systems that demand they sacrifice everything and receive nothing in return. It’s not rebellion—it’s survival.

And yet, in the United States, 4B has been eagerly repackaged as a bold feminist stance, a trendy rejection of patriarchy that fits neatly into Western narratives. Here, the movement is reduced to its catchiest elements—“no men, no love”—and stripped of the pain, exhaustion, and resignation that define it. The push to adopt 4B in the West reflects a familiar pattern: a tendency to appropriate non–Western struggles without understanding them, flattening movements like 4B into a one–size–fits–all solutions for global feminism. But 4B cannot be understood outside the context of Hell Joseon, and in Korea, feminism itself is not an empowerment slogan—it’s a liability.

What Western feminists often miss is that 4B isn’t a rejection of men—it’s a rejection of the roles imposed on everyone under Hell Joseon. Korean women opt out of dating and marriage because these roles demand too much unpaid labor and emotional sacrifice, trapping them in cycles of exhaustion. But Korean men, too, are victims of this system. Military conscription demands two years of their youth, subjecting them to brutal hazing and psychological scars. The hyper–competitive workplace doesn’t reward their sacrifices—it exploits them. Men in Hell Joseon are breadwinners not by choice, but by expectation, crushed under the same cultural weight that breaks women.

4B doesn’t pit men and women against each other; it critiques a system that ties everyone’s hands. But when the United States reframes 4B as an anti–male, anti–patriarchy stance, it turns a nuanced movement into a caricature of misandry. This framing not only erases the shared suffering in Hell Joseon but reinforces the false idea that feminism is inherently antagonistic.

For many Korean women, rejecting marriage, children, and relationships isn’t a bold choice—it’s a reluctant acknowledgment of a system that leaves no room for alternatives. The American obsession with “freedom” and “choice” misunderstands the core tragedy of 4B: the realization that the system doesn’t allow women to have it all. In Hell Joseon, a woman who chooses marriage sacrifices her career. A woman who chooses her career forfeits her family. And a woman who wants both is punished by a society that demands perfection in every role but offers no support for any of them.

4B is an obituary for dreams that Hell Joseon made impossible. It’s not a rejection of love or men—it’s a rejection of a system that asks for everything and gives nothing. And yet, in the United States, it’s turned into a lifestyle trend, a hashtag, a shiny export like K–pop and Korean skincare. This isn’t solidarity. It’s appropriation dressed as admiration, a failure to understand that 4B isn’t about empowerment—it’s about endurance in a nation that doesn’t let you rest.