You might not immediately recognize the name Gena Rowlands, but I bet your favorite actor probably does. Rowlands, best known for her revolutionary work in her husband John Cassavetes’ films, passed away on August 14th at the age of 94. And while she may be best known to most people as playing older Rachel McAdams in The Notebook, there have been few actors as impactful as her in the past sixty years.

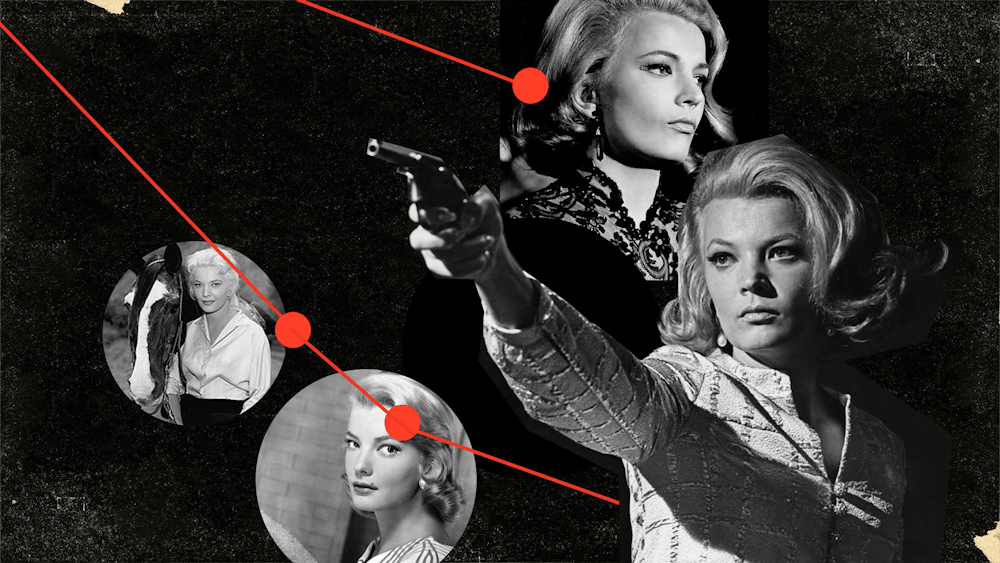

Rowlands starred in eight of her husband's films, starting with small roles in 1958’s Shadows, 1963’s A Child is Waiting, and 1968’s Faces. However, it’s Cassavetes' later films, 1971’s Minnie and Moskowitz, 1974’s A Woman Under the Influence, 1977’s Opening Night, 1980’s Gloria, and 1984’s Love Streams that cemented Rowlands as a true great among greats. What is perhaps most fascinating, and ultimately sweet, about their partnership is that it was one born out of a need for artistic expression that simply wasn’t possible before.

In a time when Hollywood routinely cast out actresses as soon as they even approached middle age, and the roles they did offer to women were typically hollow and underwritten, Rowlands was able to collaborate with her talented husband to fully express herself artistically. Rowlands was a formidable talent, easily living up to the challenging and knotty words Cassavetes wrote. Most of their films were produced independently, financed by mortgaging their own house, and this artistic desperation is clearly apparent in their work. They needed each other in a way few artists have, and their collaboration tapped into a kind of greatness, a level of realism and raw emotion that was palpable then and remains palpable today.

In particular, Rowlands’ work in A Woman Under the Influence as Mabel Longhetti, a suburban housewife undergoing a kind of mental break, is among the most influential work at a time when the art of acting was changing forever. The craft of acting was moving away from classically trained stage actors like Laurence Olivier and towards more naturalistic performers like Jack Nicholson and Al Pacino. Similar to how Marlon Brando’s work throughout the 50’s and 60’s inspired a generation of actors and filmmakers, the authenticity in Rowlands’ work continues to influence actors today. We would not have Cate Blanchett, Jennifer Lawrence, or Denzel Washington without Gena Rowlands. She fundamentally changed the way we imagine what an actor can be, the emotions they can access on screen.

Another notable performance of Rowlands’, and my personal favorite, is as Myrtle Gordon, an actress in the midst of a midlife crisis on the verge of opening her new play, in Opening Night. Rowlands brings her usual emotional intensity and nuanced look at a woman in crisis we rarely see elsewhere in film, but Opening Night, more than any of their other films, allows Rowlands and Cassavetes to explore the craft of acting and the toll it can take on performers.

In the film, Cassavetes plays Maurice, another actor in the play-within-a-play (or, more accurately, film) that Rowlands’ Myrtle is in. Their work together, and in particular their chemistry, is astonishing. They share only a few scenes together, a repetition of a single scene in the play that gets mangled and twisted as Rowlands’ character continues her descent into madness, but the added context of their off–screen relationship mixed with the on–screen subject matter brings their scenes to a new level entirely.

The central fictional play, aptly titled The Second Woman, is about an aging woman coming to terms with her place in the world and attempting to find peace. Rowlands’ character goes on a journey mirroring the woman in the play, needing to come to terms with fame and her unsteady place in Hollywood as an aging star, particularly after witnessing the death of a young fan. In many ways, it plays like Rowlands’ and Cassavetes’ creative treatise, their attempt to decry the misogyny embedded in the Hollywood system as well showcase all the industry and the public are missing out on by disregarding a whole subset of actors like Rowlands. It is clearly a personal diatribe, with the commentary on industry misogyny, and with the commentary on alcoholism in entertainment—which is poignant, considering Cassavetes struggled with alcoholism throughout his life. Much of the commentary in the film feels like Cassavetes and Rowlands working through their relationship in real time in front of us all.

Opening Night also contains the duo’s most contained and concise thoughts on the craft of acting. Throughout the film we see how much performing this role every night takes out of Rowlands’ character. We see how she’s resorted to alcoholism and a dependence on shallow, surface level relationships to get her through her day. It is as if her life on stage has taken precedence over her life off of it, like her emotions as an actress have replaced her emotions as a person. Rowlands and Cassavetes express their belief that art ultimately cannot be made halfway. Cassavetes and Rowlands poured all of themselves into each film they made together and Opening Night is the film in which they reckon with that fact.

More than anything, however, Opening Night showcases Rowlands’ brilliant craft. A scene about two–thirds of the way through the film, in which Rowlands is forced to confront the ghost of the young fan she saw killed, is among the most harrowing and raw scenes I’ve seen. Rowlands channels a level of both ferocity and sadness few other actors have ever tapped into. And on the titular opening night, Rowlands’ character quickly deviates from the script, making Cassavetes follow her ramblings and musings about life and aging in a sequence comparable to overhearing a real couple fighting about something so personal that viewership feels like an invasion of privacy.

Cassavetes passed away in 1989 from complications with cirrhosis caused by years of alcoholism. Rowlands continued working, taking parts in Hollywood films and working in films made by her son, Nick Cassavetes (such as The Notebook), but nothing she did would ever live up to the work she made with her husband. Their work, and particularly Rowlands’ acting, continues to live on past their passing.

Rowlands transformed the craft of acting into a kind of modernity no one before thought was possible. She was truly one of one.