The claim that 2024 is a lackluster year for the Cannes Film Festival has been heard throughout the two weeks of the festival, even with body–horror freakout like The Substance or emphatically political thriller The Seed of the Sacred Fig, the latter of which gained a nearly 15–minute emotional standing ovation after its premiere. Most main competition films, according to my fellow journalists, are dull and horribly nostalgic.

The claim is not without its validity, given that 2024 is indeed the year that we have fully emerged from the shadow of the pandemic but are still burrowed within a creative crevice that resulted from the prolonged lockdown. The gap also manifests itself psychologically, as filmmakers around the world are still processing the spiral effect of COVID–19 that seems to assert its presence of de–globalization, mistrust, and conservatism beyond medical discourses.

Films, like all mimetic mediums, reflect but also participate in public conversations. Festival de Cannes, the crown jewel of the world festival circuit, has emphatically made its mark and decisively shaped that conversation. What is happening, then, to our world cinema, according to Cannes?

The Decline of White Nostalgia

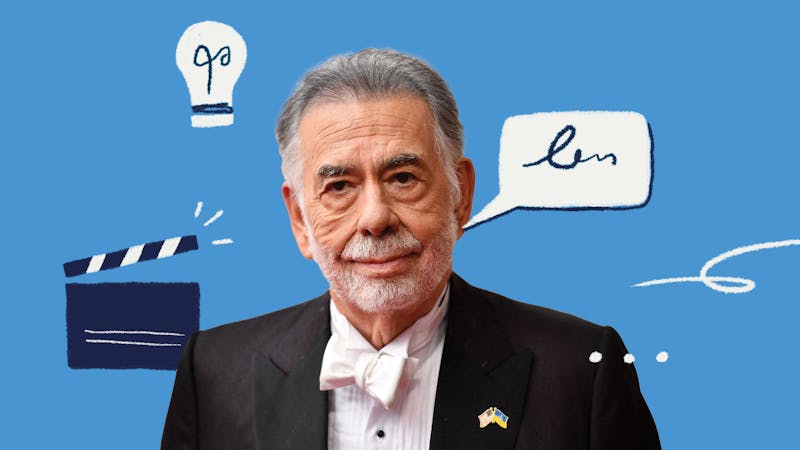

A major source of disappointment in the main competition is a collective let–down by the canonical—hence white and masculine—masterminds of film history, led by, arguably, Francis Ford Coppola’s Megalopolis, which has been 40 years in the making and since gained unparalleled hype before its premiere. Unabashedly titled Francis Ford Coppola's Megalopolis: A Fable, it is a straightforward outcry against the declining democracy typified by money politics and mobocracy of the present world, as Coppola unsubtly constructs a “New Rome” that looks identical to New York. What Coppola proposes in alternative, however, is nothing new but a nostalgic return to the rule of the clever few, as he superfluously quotes from Plato, Shakespeare, and Emerson. Similarly, despite the film’s sumptuous imagery of futurism and Art Deco decoration, the utopian city of “Megalopolis” Coppola conceives sadly looks more like a piece of real property advertisement from the 1980s.

The film, hence, strikes more as a conservative indignation masked in an abstracted and hollow hope towards the future, a glorious but overpriced flop that wants to speak nothing about the present crisis we’re in. While some may be touched by his impassioned and strangely innocent defense of the “beautiful and the impractical,” I can’t help but see it as a good–for–nothing remnant of the past—because, according to the visionary Cesar Catilina played by Adam Driver in the film, marriage is the only useful institution to preserve in his panacean utopia.

A similar nostalgia perpetuates this year’s main competition selection, from Paul Schrader’s Oh Canada to David Cronenberg’s The Shrouds and Paolo Sorrentino’s Parthenope. While Schrader dwells in the character Leonard Fife’s (and arguably by extension, his own) youth and romantic affairs, Sorrentino indulges in his hackneyed wistfulness for Naples, Italy by problematically allegorizing a female character’s life into the history of a city. Parthenope is not a bad film per se, especially given Sorrentino’s decadent camera movement that constitutes the best piece of advertisement for Southern Italy (and a much more enchanting place for visit than Coppola’s unimaginative utopia)—and I am frankly moved by Sorrentino’s anxiety over creative alienation and futility of tragic love—but there’s no denying that it is a hopeless film of the past.

Cronenberg’s The Shrouds may be the slightly interesting one among the “old films” of the year: Similarly dedicated to the director’s deceased partner like Coppola’s Megalopolis, The Shrouds tells a more humbled story of mourning, rather than an unmediated ambition for genesis, and explores the phantom materiality of the body in decomposition after death. Casting Vincent Cassel as, well, himself, Cronenberg processes his own grief in relation to modern technology that demystifies all. While once at the forefront of imagining our post–human condition, Cronenberg is now indeed feeling inadequate to make sense of the bizarre progression of modernity. While at times movingly soft, The Shrouds ultimately fails to live up to its promise and gradually descends into a cringe–worthy subplot of a conspiracy theory that is as puzzling as it may be heartbreaking.

A final addition to the hall of disappointment—and my least favorite of all—is Yorgos Lanthimos’ star–studded Kinds of Kindness. Albeit having obviously been given unrestricted creative freedom and resources (as it’s one of the longest films in this year’s selection at 165 minutes), after the commercial successes of The Favourite and Poor Things, Kinds of Kindness is a nostalgic return to Lanthimos’ earlier, signature Greek–Weird–Wave style of deadpan parody and usual theme of “consent and control.”

However, his early work was still commenting on the world we dwell in. Dogtooth, for example, explores the parallels of familial and political totalitarianism through a psychoanalytic fixation on teeth and the politicized potential of language—a theme explored by The Seed of the Sacred Fig in this year’s main competition much more poignantly. Kinds of Kindness, on the contrary, is plainly a Lanthimos–themed playground, best likened to, as far as it may seem, Martin Scorsese’s theme park comment on Marvel. The film is horribly detached from reality, with an annoyingly meticulous and spotless setting. Instead of saying something—anything—Lanthimos is bent more on playing his own sand–table game of manipulating characters into pointless madness and transgression.

The Rise of Imaginative Potentiality

What renders the collective nostalgia of our cherished auteurs even more problematic is the pronounced presence of another collection that faithfully observes our reality and proactively participates in imagining a better future. Sean Baker, who received this year’s Palme d’Or for his new romcom Anora, has dedicated his entire oeuvre to the de–criminalization and de–stigmatization of sex workers, as well as a genuine investigation into their circumstances in a capitalist society, without a trace of condescension. For me, Baker (at his best in, for example, The Florida Project) is always asking “what if”: What if our world doesn’t have to be like this? What if our children can actually have a better future? Two of my favorite works in the main competition, Andrea Arnold’s Bird and Payal Kapadia’s All We Imagine as Light, similarly tap into the power of imagination and are arguably the most tender yet empowering works of this edition of Cannes.

Bird, directed by British filmmaker Andrea Arnold (who also received the Carrosse d’Or of this year’s Directors’ Fortnight), looks into the life of a brother and a sister. Together, they are raised alone in a squat in northern Kent by an excessively young and unready father (Saltburn’s Barry Keoghan) and face an interaction with a mysterious bird–man (Undine’s Franz Rogowski). One of the most neglected films in this year’s selection, Arnold’s Bird brims with complicated emotions, indelible performances by Keoghan and Rogowski—the best casting ever across all the films in this year's Cannes—and incisive commentary into a hereditary and institutional plight of negligence and precocity, all hidden behind the tender, melancholic, but magical gaze of the bird–man.

Alternative to Arnold’s investigation of the geography of English countryside, Payal Kapadia’s poetically–titled All We Imagine as Light (which won this year’s “second–place” Grand Prix) portrays the city of Mumbai, India like never before. Drawing inspiration from his last work—A Night of Knowing Nothing, a political documentary told through a dreamy and personal lens—Kapadia superimposes scenery shots of city streets and public transportation with the soft words, murmurs, and quick banters of her characters, who are tinged with authentically documentarian sensibilities. The film’s protagonists, three nurses of different backgrounds, are both adapting themselves to the daunting city filled with unrealized fantasy and unfulfilled promises while also—like the superimposition suggests—imagining, molding, and queering their environment into a potentially habitable place for all.

Herein lies the true potential of this group of films: As female filmmakers, Arnold and Kapadia aren’t just portraying empowering female characters; instead, they’re imagining how we can alternatively see—and queer—the world, from a non–normative perspective. If the “masters” of cinema like Coppola are still living in the entrenched past glory, a new generation of filmmakers like Kapadia is already radically stepping away from their legacies into a future of potential. As the name of Kapadia’s film suggests, as long as we’re still imagining a better future, the light won’t be far away.

The Call of the Real

It’s hard to ignore the usage of “real footage” in this year’s selection at Cannes, from TikTok and phone–shot portrait videos, to Zoom recordings and archival footage. Realism, as one of the longest artistic traditions, is a defining feature of the art of the moving image, which imitates our reality like never before seen in painting and literature. Our often unconscious perception of the real in film is indebted to the neorealist aesthetics of, for example, the handheld camera, natural lighting, and on–location shooting that originated from Italy in the 1950s.

However, when the means of image–making and image–dissemination are again democratized through infrastructure like phones, 5G networks, and social networks, the definition and value of the real in film becomes increasingly contested. If we can already see the “real,” arguably the most real, through TikTok videos, why do we still need realist films?

The direct response to the conundrum is to incorporate TikTok and portrait videos into the grammar of filmmaking. While it’s often naturally deemed to be “uncinematic” to show portrait video on a wide screen, a lot of the films in Cannes this year prominently feature them: Arnold’s Bird, Mohammad Rasoulof’s The Seed of the Sacred Fig, Lou Ye’s An Unfinished Film. The latter two present a helpful contrast in understanding how realist filmmakers nowadays are coping with a call for the “most” real. While both films investigate political and social movements in a contested environment (Rasoulof portrays the “Woman, Life, Freedom” movement in Iran, while Lou reflects on the democratic protest in China following the tightening lockdown), their usages of “real footage” are in starkly opposite manner.

Rasoulof, on one hand, directly employs TikTok and Instagram videos of real footage of the protest. We see the characters looking at their phones in anxiety, and the film then immediately cuts to a portrait video of what the character is looking at in the diegesis. The film ends with a political statement of the death of the patriarchy and a call for freedom; following the end of the film, we also see a wide array of portrait videos showing the extent of the protest. The “real footage,” in this sense, is used as evidence of or substantiation for the “realistic” quality of the film—when neorealist aesthetics cease to be effective, filmmakers like Rasoulof turn to such footage to add to the power of the narrative.

On the other hand, Lou employs real footage as a destabilization. Instead of using such footage as a source of validation, Lou participates in a task of media archaeology, as he presents a collage of all kinds of footage, ranging from video calls, propaganda advertisements, TikTok videos, and popular songs as well as banned songs—a mix of good and bad media, in our conventional division. Instead of contributing to an unambiguous statement like Rasoulof does, Lou’s film, for me, involves a more chaotic and complicated job of destabilization and, by extension, politicization.

Real footage, however, can also be used to achieve diverse purposes beyond reality, and in this year’s selection, Miguel Gomes’ Grand Tour and Jia Zhangke’s Caught by the Tides present dazzling usages of archival footage. Both at the forefront of the independent artistic revolution of today’s world cinema, Gomes and Jia surprisingly converge in their choice to veer into media collage rather than straightforward storytelling. Grand Tour, on one hand, juxtaposes a colonial travelogue of a British public servant’s journey in East Asia in 1917 with real footage unambiguously shot in the present, with images of masks, phones, and highways. Grossly heterogeneous and incompatible with the delirious “oriental joy” that Gomes appropriates, the real footage in effect rewrites colonial history from a contemporary lens. In Caught by the Tides, on the other hand, Jia unearths materials he shot across his entire filmography, all the way from the 2000s for Platform and Still Life, in order to blur the boundaries between staged performances and real footages and create an adamant epic for those caught by the tides of the breathtaking and at times horrifying advent of modernity in China over the past 20 years.

Why realism? And, frankly, why do I dislike Coppola’s Megalopolis so much? One startling realization during my Cannes experience this year—especially after flying from Penn's campus, days after the Gaza Solidarity Encampment was disbanded through arrests—is the complete absence of discourse on the war in Gaza. No film depicting the conflict or participating in the discussion is chosen among the selection of the year, and there isn’t even a pavilion for Palestine at the international village of the film market. Despite growing tension for potential protests and speeches during the festival, Thierry Frémaux, the artistic director, has successfully managed to make sure that the “main interest … is cinema,” with possibly only the exception of Cate Blanchett’s subtly–modified dress.

The bloodshed, however, goes on despite Cannes’ refusal to foster discussions. Similarly, Megalopolis—along with all the “old nostalgic flicks” of this year—refuses to dive into an often thorny reality and instead resorts to an easy way out. To keenly observe and represent our immediate reality, in this sense, is only the first step in a long journey of searching for a better future. And as I’ve demonstrated with this piece, realism does not equate to a strictly realistic portrayal—it can be imaginative, romantic, destabilizing, and even confusing, full of dazzling possibilities explored by some of our finest filmmakers around the world, from Arnold and Kapadia to Lou and Jia in Cannes. Instead, it represents a commitment to our emphatic reality, and, for me, a hope in humankind’s ability to eventually take the right path.