Some people keep diaries; I keep sketchbooks. On days when I’m home from school and nostalgia has dug its Crayola–stained fingers into my thoughts, I pull them from the shelf and begin a trip through time.

My first truly dedicated and dated sketchbook is a dark green Strathmore made of recycled paper, spiral–bound, and identical to those you can still find at your local Michaels. Even before reading the Sharpie on the cover, I can tell you it’s from middle school; the double–story lowercase “a” in “7th–8th grade” doesn’t match with how I write the letter now. The pages are filled with pencil drawings I made during recess, in the backyard, and on road trips. I probably asked my parents to buy me a sketchbook after doodling all over my pre–algebra homework. Perhaps my favorite page boasts an unfinished golden retriever on one side, and my notes from a field trip to a waste–to–energy power plant on the other.

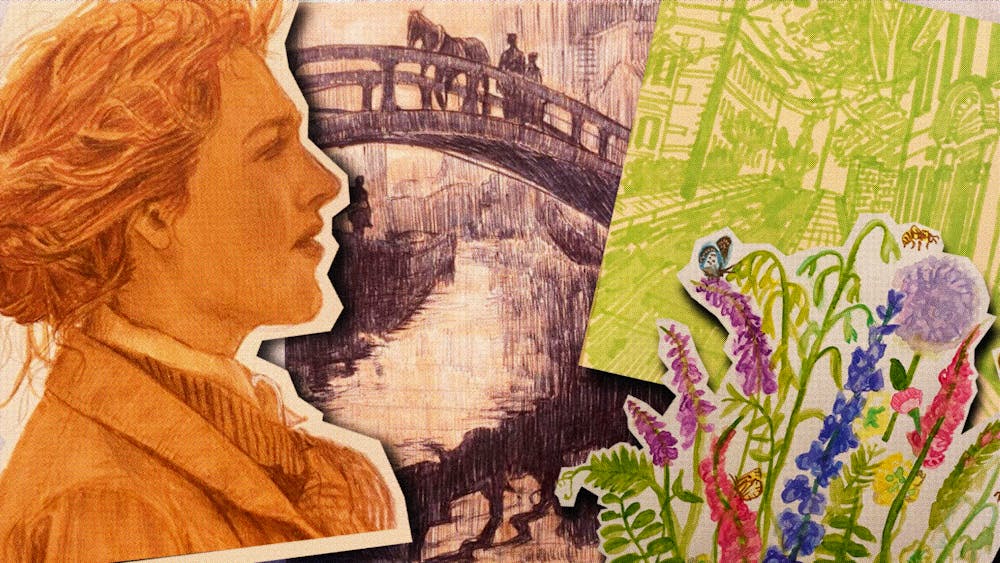

I’ve continued to keep sketchbooks ever since. Flipping through them, I can look back at how my skills have developed over the years. But these messy, often unfinished drawings and colorful doodles also illustrate my journey through life. While examining my old art, I cringe, I laugh, I occasionally admire, and I remember. I’ve only taken one art class in total between both high school and college, and my sketchbook entries are far from consistent. Holding onto that hobby, though, has allowed me to be creative and find joy in my mistakes—all while keeping, and even celebrating, the evidence. Art has helped me learn to be bad at things and keep at them. It has encouraged me to work with my hands and create something more physical than Word Documents or PDFs submitted to Canvas. I’ve been disappointed in the outcome of so many of the pieces I have created, but the disappointment doesn’t outweigh the delight of creating. Rarely can I capture on paper or canvas exactly what I hoped to achieve in my head, but each time I inch closer to that goal, I feel rewarded for my efforts.

Traditional art is especially close to my heart because there’s no way to make your errors completely vanish, even with an eraser; there’s no “Ctrl+Z” to undo a portrait’s disproportionate eye or a watercolor landscape’s muddied colors. You have to work with the process, not against it, and let go of perfectionism. In common use, the word “amateur” means “a person who is incompetent or inept at a particular activity.” But at its roots, it is not a derogatory term. Amateur originally comes from Latin’s “amator,” which means “lover.” Creating art because of our pure love for it is, to me, anything but foolish.

In our undergraduate years, we’re encouraged to join clubs and organizations that cultivate our non–academic or preprofessional interests. But, I think it’s precious to also have something that is just mine, completely severed from reliance on overlapping Google Calendars and the participation of others. During my first semester on campus in the spring of 2021, I felt isolated, despite being surrounded by other first years. The doldrums of life on Zoom felt like anything but what I had been promised in college. The visual arts were maybe the only part of my life that remained steady, and I took refuge in the familiar routine of putting pencil to paper. It was a rare form of self–expression in a time and place where you couldn’t even read the expressions beneath the masks on other people’s faces.

While creating is a deeply personal experience, art is also essentially communal. For every artist who claims to be self–taught, their art holds the influence of murals on the sides of buildings, the instructions on a pack of oil pastels, and the inspiration gleaned from the colors and shapes of the world around us. I rarely show my sketchbook to others, and when I do, it’s hard not to clamp the rest of the pages shut so my friends don’t see the work I’m less proud of. Visual art can be as private as you’d like, but if you truly enjoy it, it touches other aspects of life. Not all of my art still sits in my childhood bedroom. I can’t even remember all of the handmade birthday cards, paintings, and crafts that I’ve gifted to family and friends over my 22 years of life. Most of them would probably embarrass me now, but I’m warmed by the experience of creating and giving.

Two years ago, after much deliberation, I created an Instagram account for my art. I haven’t used it to sell anything, and I also haven’t tried gaining many followers—it has less than a quarter of the number I have on my personal account. But, I decided to make it because I want to share what I’m creating. I did it for myself, too, to keep track of my efforts as a true amateur who loves drawing and painting just for the sake of it. It’s tempting to say my art page is just an online version of my sketchbook, but in truth, it’s a highlight reel.

Art museums are, in some ways, an illusion. We walk around and gaze at finished masterpieces revered by critics and public alike; they occupy the walls like a "greatest hits" album of art history. What we don’t see is the blood, sweat, and tears—the eraser shavings, crumpled–up attempts, and thumbnail sketches—that led to them. Every artistic treasure is just a snapshot in their creators’ decades–long careers.

Last summer, I visited an exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art that was dedicated to Vincent van Gogh—and more specifically, the development of his cypresses, a major motif in his art. The show included his most famous work, The Starry Night, painted in 1889, in addition to several other gorgeous oil paintings. However, what I found most extraordinary was the space the exhibit gave to his both on–and–behind–the–canvas progress. In letters to family, van Gogh articulates the challenges of capturing the cypresses. One image even seems to appear three times—a Wheat Field with Cypresses painted in July of 1889, a replica using reed pen on paper, and then a studio version from September of that year that’s lighter in tone overall. I visited the exhibit twice, just to see the Dutch artist’s growth and his conscious reworking of techniques and ideas: the proof of his artistic imperfection.

I have nearly a decade's worth of sketchbooks now, and I plan to continue buying, ruining, and beautifying them no matter where I am in life. In fact, I recently got a new one—it’s sky blue, 13 by 21 centimeters, and full of blank pages. I also just bought a cheap set of gouache paints. They’re like a thicker watercolor, opaque and bold and vibrant. I’ve never used them before, so I’ll probably fail at it. As an amateur, I’m excited to try.