It’s easy to forget erasure. It’s easy to get blinded by the popularity of films like Everything Everywhere All At Once and Minari sweeping awards, K–dramas adorning the Netflix front page, and K–pop topping the Billboard charts. Why harp on past racism when we can move forward without turning back?

Historically, famous examples of erasing asian stories include Richard Barthelmess as Cheng Huan in Broken Blossoms (1919) and Mickey Rooney performing a caricature of I. Y. Yunioshi in Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961). The white–washing in these instances was literal, as white actors physically took up the space designed for but never given to Asian individuals.

The Academy Award is another story. In addition to a severe absence of Asian actors in nomination and award, erasure at the Oscars also manifests as a gross misrepresentation: Performances are only lauded when they flatten Asian history, experiences, and culture through the eyes of the white audience. For instance, prior to Yuh–Jung Youn in Minari in 2020, Miyoshi Umeki was the first and only individual of Asian descent to win Best Supporting Actress. In the film Sayonara (1957), Umeki, of Japanese descent, is engaged in a forbidden interracial marriage with a white American airman. A racial slur is used in reference to the character Umeki plays. In another scene, while wrapped in a towel, she bathes her love interest Kelly, and remains soft–spoken and shy.

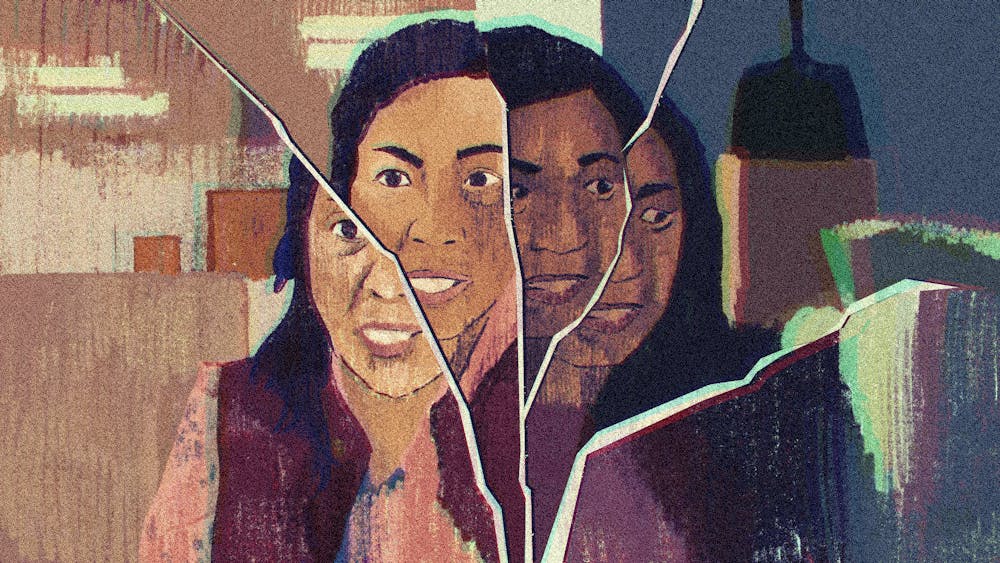

Umeki was faced with the choice: being invisible all–together or to be seen through the post–World War Two Era stereotypes of Japanese women: docile and doll–like.

Now, we have titles we can point to as successes and films we can relate to. However, a report by the Annenberg Inclusion Initiative indicates that this isn’t enough. Of the 1,300 top–grossing films analyzed from 2007 to 2019, only three directors were API women. On–screen, of 51,000 speaking characters, 5.9% were API. This figure is made worse when considering representation for intersectional identities such as those who are LGBTQ or disabled.

Furthermore, recent titles and successes predominantly come out of a select few East–Asian countries. Due to the broad umbrella term of “Asian,” we celebrate these successes in broad strokes that smother other identities.

Nonetheless, there are some successful films of recent that are celebrated by the industry and yet have also endowed nuances to their representation in already impactful scenes. Adding depth and context, these films feature representations that extend from events I can directly relate to, to something acknowledging the generations of Asian stories that were erased from the screen.

Joy/Jobu Tupaki in Everything Everywhere All At Once explains, being right is “a small box invented by people who are afraid. And I know what it feels like to be trapped inside that box.” In the film, the actress Stephanie Hsu portrays someone who feels trapped by expectations of society, their parents, and themselves. Joy’s message also represents the many difficult choices Asians have had to face in Hollywood. If their one shot to live by their passion is within a box of stereotypes, should they take the opportunity? Is “bad” representation a detriment to “Asians” as a whole, or is Asian representation on screen itself already meaningful enough?

When Joy/Jobu Tupaki in her lowest moments just wants someone to understand her pain, we are once again reminded of the context surrounding this film. In a world filled with complex emotions and experiences, we desire empathy through film to reflect real life, the real lives of myriads of people. This entails learning from the errors of the past and developing apt representations that can reflect the complexities of what it means to be a person—not just “Asian–experience” born out of people’s general assumption and imagination.

That being said, recent successes do deserve to be unabashedly applauded and enjoyed. While I know I shouldn’t put so much stock into the Oscars as a body of prestige, my emotions didn’t share this rationality when I watched the Academy Award ceremony earlier this year for Everything Everywhere All At Once—a story that resonates with me so strongly, that brings me to tears with every rewatch. To see that emotion validated as having value in the world of critics and high–art is unparalleled. Seeing the elation of people’s work acknowledged on one of the largest platforms for film gives me a sense of pride and confidence in the value of my ideology and experiences.

Through acknowledging the history that came before these precious moments, it is important to use them as key reminders to constantly find ways to uplift and support more diverse Asian stories.