"To collect photographs," wrote Susan Sontag in her book On Photography, "is to collect the world." Photography has always fascinated me, particularly in one specific context: when photos adorn book covers. While the saying goes "Don't judge a book by its cover," I can't resist an enticing visual. Hanya Yanagihara's 2015 novel, A Little Life's cover, achieved just that for me. The book delves into the lives of four college friends as they navigate the turbulent waters of success and suffering in New York City.

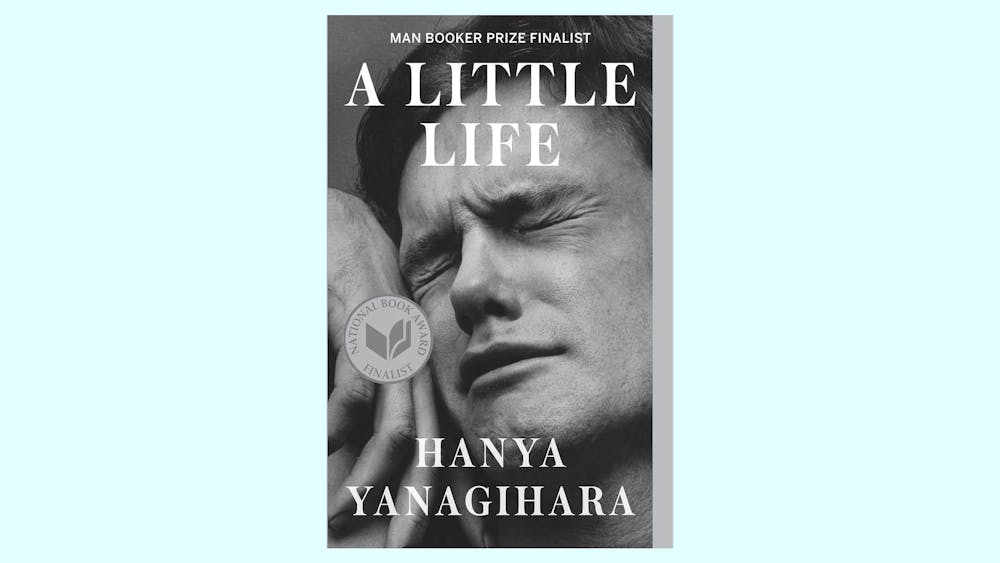

The black and white photo of a man with his eyes forcefully closed and his hands gently pressed against his cheek caught my attention. I couldn't discern whether the expression etched on the man's face came from a feeling of pleasure or physical pain, as he was about to burst into violent tears. The curious image is Orgasmic Man by Peter Hujar, which depicts ecstasy and male vulnerability.

The play of light and shadows on the model's light skin creates volumes that remind me of marble sculptures. The way the model's hand rests near his face is as delicate as Michelangelo's statues, such as the Dying Slave and the sleeping Fauno Barberini. However, the face in the photograph doesn't follow the classical style; it's more intense and expresses strong feelings of ecstasy or suffering. These mixed senses create tension in the photo, and the title, Orgasmic Man, is a clue to understanding it.

In the year of the photo, 1969, a wild storm of change was brewing. This was the year of the famous Stonewall riots in the heart of New York City, when the LGBTQ+ community protested after a police raid and sparked the modern queer civil rights movement. Amid this backdrop, Peter Hujar was on a mission. He didn't just click his camera at the colorful characters of the NYC downtown scene he called home; instead, he saw them as vibrant souls worthy of deep respect for being unapologetically themselves. Hujar's photographs weren't just about a homoerotic gaze; they were about shouting, "This is me!" in a world where identity was both a political statement and a personal journey. His art isn't just pictures; it's a snapshot of a cultural revolution.

In the captivating dance of agony and ecstasy, Hujar's portrait captures a man whose face is like a canvas of complex emotions. It's a reminder of the dual nature of homosexuality: hidden, suppressed, and at times punished. It raises questions about the price one pays for being true to themselves and facing the harshness of homophobia. The shadow of the AIDS epidemic, especially during the '80s and '90s, tragically claimed the life of Peter Hujar. The picture underscores the intimate connection of the time between being gay and the constant specter of death.

One of the most influential photography critics of her time, Susan Sontag met Hujar back in 1963, and they quickly found a shared artistic sensibility. According to Sontag, "Peter Hujar knows that portraits in life are always, also, portraits in death." Through Hujar's lens or the lens of the AIDS crisis, you see death weaving its threads through the entire image, infusing it with a profound weight that speaks of lives fully lived and memories tragically shattered. It's like peering into the soul of a generation marked by love, loss, and defiance.

At first glance, when I laid eyes on Orgasmic Man on the cover of A Little Life, I thought, "This book must be about pleasure." Yet, Hanya Yanagihara's choice of this particular photo for her novel's cover seemed to hold more depth than met the eye. As Yanagihara herself stated in a Wall Street Journal review: “I really hung on for the cover. … There’s something so visceral about it.”

A mediocre photograph provides a sense of comfort, offering the expected. But a truly exceptional photograph, like Hujar’s work, is a disruptive force. It's not merely a picture; it's an emotional earthquake. It disturbs, it gets under your skin, it's heart–wrenching, and it's powerful. Yet, paradoxically, it's also cathartic, moving, unforgettable, and transformative.

This photo's allure lies in its inherent uncertainty, a pendulum that swings back and forth between ecstasy and agony. I found myself in that same state of ambiguity, unsure if I was trespassing on an intimate moment. As I finished A Little Life and considered the cover within its context, I realized, "No, it's about pain." Ultimately, I concluded it was about both, but by then, I couldn't tell if I was describing Hujar's portrait, Yanagihara's book, or simply life itself.