How do you untangle your existence from someone you’ve built your life with? It’s especially difficult when, every time you pick up your phone, you look for their notification, hope they posted an Instagram story meant for you, or somehow snuck their way into your profile views. We’re always hoping to see our ex’s name on our screens, but do our expectations end there? Was our relationship dull enough that a story view makes our hearts drop? Or is this just the accepted contemporary alternative to grand gestures and delivered flowers? The hyperconnectivity between us and past relationships through the mediums of the digital age collapses the mystery, drama, and closure that exists in the turbulence of a romantic ending. Break–ups are boring—because it’s simply become too easy to check up on your ex.

When we had no idea what our exes were up to—only hearing about them from a friend of a friend or through a mention in print—not only were we able to detach ourselves from our ex–partners, but there was always the possibility of a sweet serendipitous reunion with them at any given moment. You could hope that one day that person and you find each other again under better circumstances at the right time. That glorious reunion, you thought, would be so beautiful, so emotionally relieving, that it would feel like art. That is exactly what happened when German performance artist Ulay sat across from his ex–lover and collaborator Marina Abramović at her 2010 performance retrospective The Artist is Present.

Abramović met Ulay in 1975, two 30–something European performance artists both immediately taken by one another. Abramović in her book, Walk Through Walls, describes their connection as not created, but rather innate. Their hearts beat as one, she explains. Their eyes locked and they were forever changed. No Instagram story liking, swiping right, or game–playing is necessary.

There’s no denying that the lack of mystery in break–ups is aligned with the lack of mystery in relationships. Ulay and Abramović’s love story was far from dull. Separated by their busy schedules as artists, they spent hours on the phone, tape–recorded by Ulay who knew their love would be worthy of documentation from the start. But when phone bills got too high, the couple began letter correspondence, a lost art among the average iPhone–carrying couple. Unable to spend time apart, they began planning how to create art together, fitting one another seamlessly into the other's lives. Their “hard launch,” to mirror digital terminology, was Relation in Space, a 58–minute performance piece at the XXXVIII Biennale in Venice, Italy. The artists stood naked twenty meters apart, and ran into one another, capturing the sound of their flesh colliding with a microphone, transferring their energy and transmitting their love between their bodies with each collision.

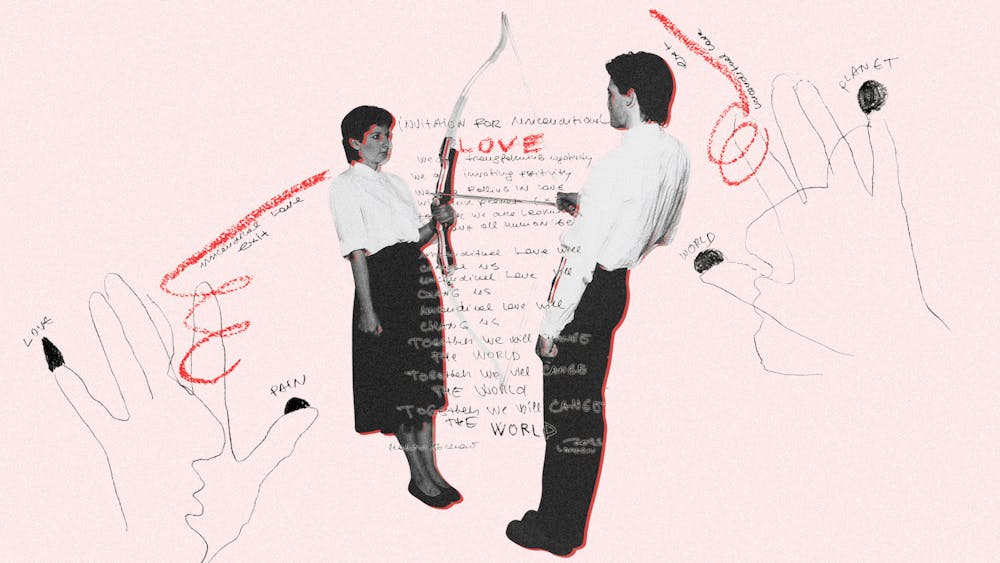

They continued with their intense love story, performing together and living out of a van they called home. Their performances highlighted their connection as well as their shared perception of the world and their desire to challenge it. At their shared birthday party in 1976, they performed Talking about Similarity for their friends. After sewing his lips together, Ulay sat in front of the audience of friends and Abramović explained that they were to ask questions, and Abramović was to answer as Ulay. Another performance of theirs among the many, was their 1980 performance of Rest Energy. Ulay held the string of a bow and arrow to the very end, the arrow pointing directly at Abramović’s heart. Both in a constant state of tension, pulling from each side, they bore the constant threat that if one of them made a mistake, Abramović’s heart would literally be shattered. Their art showed the all–consuming nature of intense, true love. The delicate balance of trust, of giving your all to someone that you are willing to put your voice, and your life in someone else's hands, knowing that if they slip up, you are immediately shattered.

In our contemporary relationships, we rarely mark the intensity of our love by how willing we are to put our lives in the hands of the ones we love. To bear ourselves completely to one another without fear they won’t accept it. We don’t perform Talking about Similarity at our weddings to demonstrate our ever–lasting commitment. We cement our relationship outwardly, rather than within our hearts. Soft launches, engagement TikTok, and pregnancy announcements flood our feeds. We feel the need to show off our love to others, rather than to each other. These external markers of love, the ones we can cautiously check our exes aren’t making elsewhere, are easily wiped away from the public consciousness. When we break up with our significant others, we can delete the Instagram posts and wipe away the public presence—but Ulay can’t erase the scars from his sewn–shut mouth, nor could Abramović ignore the mutilation her body faced in her taxing works with him.

In 1981, Ulay and Abramović decided they would walk the Great Wall of China, starting from opposite sides and meeting in the middle. Inspired and madly in love, they decided they were to marry when they reached the middle. But by the time the feat was approved and set to begin, it had been 12 years since the two instantly connected. Their lives once intrinsically connected by their love and art began to diverge, the arrow, this time metaphorical, began slipping and was bound to shatter Abramović’s heart. So, at the end of their rigorous three–month walk of the Great Wall, they didn’t get married; instead, they hugged quickly and shook hands—ending their personal and professional relationship there.

Upon returning to her home of Amsterdam, alone for the first time in 12 years, she told her friends it would take at least half that long, six years, to be freed of the pain of losing Ulay. One day soon after seeing Ulay kissing his pregnant wife, Abramović decided she needed to get out of Amsterdam—physically separating herself from the world that she built with Ulay. This separation largely allowed Abramović to continue and improve her career as a performance artist, elevating her to the highest echelon of artists on her own. This separation is what is lost in the digital age. There’s no way to fully sever yourself from someone your whole digital identity is tethered to. After spending 12 years with someone, the ability to keep checking in, and putting yourself through the wringer by watching the life you could have had with someone is grueling. It’s too hard to completely cut ties, unfollow, or move away like Abramović because stalking your ex's new life is too easy. All you have to do is pick up your phone.

But Abramović’s decisive and concrete separation from Ulay was not only geographical but professional. In her 1992 work Biography, she ended by reciting “BYE–BYE ULAY”, dramatically severing her work from the theme of their love and connection.

Years later, in March 2010, Abramović took over the Museum of Modern Art in New York, along with a prolific collection of performance retrospectives, The Artist is Present allowed strangers to connect with the artist. As wild lines form to sit across the artist, one stranger would sit across from Abramović for as long or short as they would like, maintaining eye contact, transmitting energy, pain, and love—as Ulay and Abramović did together years before. Abramović described that the sitter immediately felt very moved, they were forced in that moment to look inside themselves and confront the pain within them. In the digital age, we simply never are confronted with our feelings or our own pain. We are docile and numb, scrolling through our feeds to numb our feelings. The Artist is Present forces that uncomfortable, but necessary feeling for the participant.

On the opening night of The Artist is Present, Abramović was forced to look within and feel her pain when Ulay sat in front of her unexpectedly. As they shared the space, watched by hundreds of onlookers, Abramović explained that 12 years of her life ran through her mind in an instant. In a moment of overwhelming emotion, love, and pain, Abramović broke the rules of her performance, reaching for Ulay's hands across the table. As thousands of eyes watched their dramatic reunion—the sweet sweet reunion one dreams of when they end their relationship—Ulay and Abramović looked only at one another, their eyes swelling with tears. Ulay and Abramović were painfully separated to be beautifully reunited. They, if it’s possible, had a true romantic breakup. They made the ending of a relationship, and the trauma that comes with it, into art—not just an unfollow.