A stroll down the vitamins aisle at Walmart yields the usual: hair, nail, and skin gummies, vitamin C pills, and … wait—Ozempic? It’s hard to believe that a medication originally designed to treat Type 2 diabetes has become so normalized that it sits next to everyday supplements on shelves, is available through pharmacies, and is sometimes just a click away on online marketplaces like Amazon. The ease of access and widespread availability raises a critical question: What are the consequences when we commoditize medical treatments and sell them as easy lifestyle fixes?

As health and wellness intersect with consumer culture, there becomes a risk of promoting dangerous behaviors that prioritize profit over well–informed, safe health practices. GLP–1 drugs, like Ozempic and Wegovy, which were originally approved by the Food and Drug Administration to manage Type 2 diabetes, have been rapidly rebranded as weight–loss solutions. Their appetite–suppressing side effects have spurred social media influencers to simplify their effects, often presenting these drugs as a quick and easy path to weight loss. This shift to a consumer–driven narrative obscures crucial details, including side effects and ethical implications.

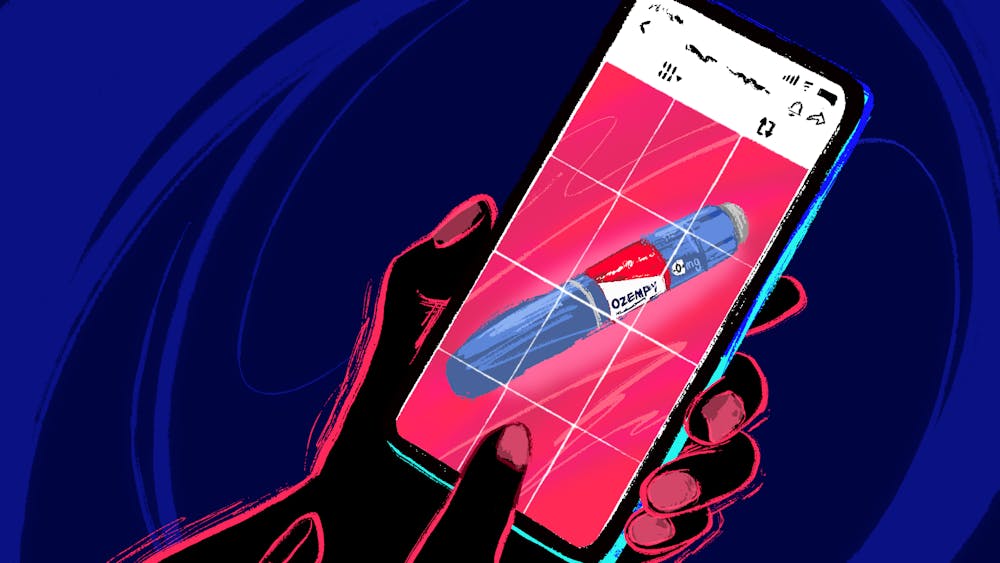

Although platforms like Instagram and TikTok can help make complex topics, like the scientific mechanisms behind GLP–1 drugs, digestible and appealing, it also oversimplifies them. Influencers post dramatic before–and–after images, recount their painless weight–loss journeys, and even provide product links—all of which encourages others to naively jump on the trend. The craze for Ozempic as a weight–loss solution, however, has come with consequences, including medication shortages that impact people who need it for managing diabetes and other critical conditions.

Those that do choose to use GLP–1 drugs for weight–loss purposes soon discover, however, how it can be hard to maintain the weight loss, as the weight will be regained if the patient stops taking the drug. On the other hand, the drug can come with side effects including nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramping, delayed gastric emptying, and constipation, making it difficult for some patients to commit to taking the drug for long periods. This less glamorous depiction of the reality of GLP–1 drugs, however, is nowhere to be found in peppy “What I Eat in a Day on Ozempic” videos or 15–second body–checking videos.

What is more concerning, though, is the invocation of the science and name of GLP–1 medications to sell imitation supplements through TikTok. Even though traditional GLP–1 drugs require a prescription, their growing demand has inspired a surge of “GLP–1 alternatives” marketed as cheaper, over–the–counter solutions. These alternatives, however, have not undergone FDA scrutiny for safety or efficacy, and the agency has issued warnings against them: “Unapproved versions [of GLP–1 medications] do not undergo FDA’s review for safety, effectiveness, and quality before they are marketed.”

When patients use unregulated drugs, they miss out on essential medical guidance, which can be critical in cases of allergic reactions or other adverse effects, including severe gastric problems and pancreatitis. Unapproved treatments also carry significant risks, as they may contain harmful chemicals or toxins.

The rising popularity of GLP–1 drugs has not only led to increased demand but also opened the door for industries to profit off consumers' desire for affordable, effective weight–loss solutions. Ozempic and Wegovy are also extremely costly, running users about $1,000 per month. When the prices are that steep, it can be easy for people to turn to cheaper alternatives, believing that they’re getting the same results at a fraction of the price, even if they have not been thoroughly tested for user safety.

For example, Hers, a brand for women’s health, has all three alternatives listed on their website. Ozempic starts at $1,799 per month, Wegovy at $1,349 per month, and an alternative option at $199 per month: Hers compounded semaglutide, their alternative to the two FDA–approved drugs. On their website, Hers states, “Compounded semaglutide is not FDA–approved. FDA does not evaluate compounded products for safety, effectiveness, or quality.” Their product description rebrands this medical technology for commercial use for weight–conscious consumers.

Celebrity–endorsed brands further complicate the blurred lines between medical treatments and commercial “wellness” products by leveraging medical terminology to sell products that mimic but do not match the effects of prescription drugs. Kourtney Kardashian’s health supplement brand, Lemme, recently launched a supplement called “Lemme GLP–1 Daily.” Despite its name, the supplement doesn’t contain any actual GLP–1 agonists. Instead, Lemme claims that this product “promotes your body’s GLP–1 production, reduces hunger and cravings, and supports fat reduction with 3 clinically–studied ingredients.” While GLP–1 drugs are scientifically validated for specific uses, supplements like Lemme GLP–1 Daily navigate a gray area, leveraging buzzwords from legitimate medical treatments to attract attention without undergoing the rigorous testing that medications face.

The normalization of health products through consumer culture, especially when amplified by influencers and celebrities, fosters a perception that health supplements and drugs are accessible, easy, and even essential for self–care. When trusted figures promote supplements that mimic medical terminology—like GLP–1—many consumers assume they are getting a comparable product to prescription medications. However, without FDA regulation or clinical validation, these supplements risk misleading people into believing in results that may be unfounded.

In an era where digital health culture is more convenient and accessible than ever, consumer interest and influencer promotion frequently overshadow the original medical intent behind many health products. As drugs like Ozempic cross over from the domain of clinical treatment to trending wellness solutions, the boundary between legitimate medical intervention and casual health fixes grows increasingly ambiguous. This shift raises significant concerns around the adequacy of oversight, the public's understanding of complex health products, and the ethics surrounding digital health advice.