A lush patchwork of green once welcomed visitors to the Arthur Ross Gallery in the Fisher Fine Arts Library. Bold brushstrokes stood firm against a fragmented sky, capturing the resilience of two pine trees whose branches stretched daringly into the expanse. They stood together, their limbs entwined as if each offered the other strength to rise higher. Their leaves, tinged with a hint of crispness, suggested a drought—a subtle nod to the hardships faced by the artist David Driskell in his formative years in Appalachia. These trees, like Driskell himself, embodied a defiant resilience, a strength echoed in his art and in his life’s work: the elevation of fellow Black artists.

Driskell’s career as an artist and curator was defined by a singular mission—to cultivate and sustain a space for Black art within the broader American art canon. His work was never solitary; it was a mosaic of collaboration, built on the conviction that Black art deserved not just recognition, but celebration. This spirit permeated David C. Driskell and Friends: Creativity, Collaboration, and Friendship, an exhibition that brought together a collection of works from Driskell’s peers and collaborators. In this exhibit, the intricate relationships between these artists came alive, woven together like the branches of the towering pines in his paintings.

The exhibition, which has since closed, was not merely a display of art; it was a testament to the fertile creative soil Driskell spent decades cultivating. His influence extended far beyond the gallery walls, beyond the careers of his contemporaries. Driskell was not just nurturing the trees of the present, but planting saplings of future artists whose roots were grounded in the legacy he left behind. His commitment to this cause has yielded a forest of artistic growth, a legacy of profound depth and scope.

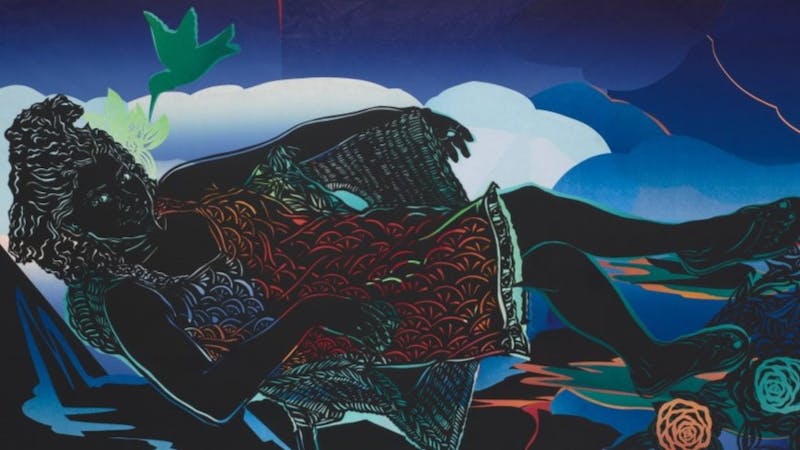

The gallery’s texture and vibrancy redefined the natural and pastoral. Claude Clark’s Mealtime captured a serene scene of a mother and daughter among chickens at dusk, their homestead glowing against the encroaching darkness. William T. Williams’ Deacon’s Day employed fractured acrylic paint to create movement and energy, mimicking the quilts found in homes similar to Clark’s Mealtime. These artists, like Driskell, harnessed abstraction’s freedom to push boundaries and develop unique artistic languages.

Driskell’s own work, including Pine Trees #5, acted as a bridge between the personal and the universal. The painting reflected his deep connection to nature and broader reflections on Black identity and spirituality. The trees, standing tall, mirrored Driskell’s belief in art’s transformative power. His legacy as both an artist and curator was embedded in every piece in the exhibition, a living attestation to his enduring influence.

Driskell’s curatorial prowess—bringing together artists from diverse backgrounds and styles—profoundly shaped the narrative of Black art in the United States. Throughout his life, he organized over 35 exhibitions celebrating the work of Black artists. The David C. Driskell and Friends exhibition at the Arthur Ross Gallery thus was not just a tribute to his legacy but a continuation of it. It was an homage to his lifelong work and an example of where his vision still flourishes.

Now that the exhibition is no longer accessible, there is a sense of loss—a loss of the harmony felt when experiencing the collection in person, walking through the gallery, guided by Driskell’s hand. Yet, Driskell’s influence remains ever–present, extending beyond the gallery walls. His work endures, not only in museums and galleries, but in the way we see the world. Each time we walk through a pine forest in Appalachia or witness the purposeful amplification of Black art, we are reminded of Driskell’s profound connection to his environment. His paintings can still be found in collections across the country, in institutions like the Smithsonian, where his vision continues to inspire young artists and viewers.

This exhibition, ultimately, offered more than a mere retrospective. It was a continuation of an ongoing dialogue of Driskell’s legacy—one grounded in collaboration, resilience, and the celebration of Black creativity. As bell hooks’ words from Appalachian Elegy echo:

“the long dead

the long gone

speak to us

from beyond the grave

guide us

that we may learn

all the ways

to hold tender this land”

Driskell’s legacy, like the pine trees in his paintings, carries the fragrance of hope and the promise of resurrection—an enduring reminder that art, like the land, must be nurtured and held tenderly. Through the works of his friends, collaborators, and future generations of artists, Driskell’s vision will continue to defy and inspire, quilting spaces with bold, enduring strokes of creativity.