In high school, I remember going through the different art movements and trying to remember what characterized each. Dadaism was the odd, scrapbook–looking one. Abstract art was the one where nothing looked like you thought it would. Impressionism was the one on light and movement, freeing the contours of their brush lines. Realism was the one that was, well, realistic. And then, there was classicism.

Classicism is the movement drawn from “classical” art and culture—that is, the art from ancient Greek and Roman times. A Google search of the word “classical” reveals that it is “regarded as representing an exemplary standard” as if to say classical art is the epitome of a desired aesthetic. But, as with many standards, that’s extremely problematic.

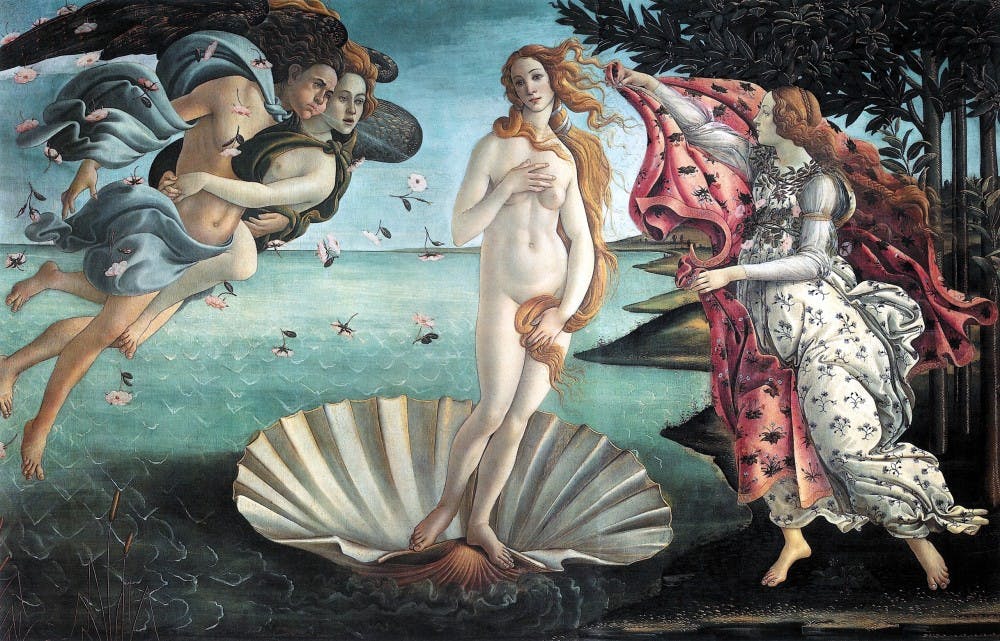

For one, the classical representation is anything but diverse. In almost every art piece, the same figures emerge: white old men. Of course, this was the case with nearly everything produced back in the day (and still is, to be honest) and the art can be said to be symptomatic of the times. Still, it does not go without saying that women as models are depicted less often and when they are, in substantially lower positions. The same goes for minority groups, racially, ethnically, and socioeconomically—whether that be seen in the size of the figures or the actual semantic content of the piece. There are exceptions to this pattern, but they’re few and far between.

Art is supposed to be this part of culture that is relatable and speaks to a wide variety of audiences. Or at least the publicly adored art. For a work to be mainstream, it has to appeal to the diversity of the audience, but classical art clearly does not fit this condition. Yet, even today, though standards are shifting towards a more contemporary and abstract take, classical art is still so often (and too often) regarded as the holy grail.

There’s also this conception that classical art is so often depicting merely scenes or people. But in looking at the context, art (or at least the means to art) was not accessible to everyone in those days. A portrait had to be commissioned. A painting was paid for. Everything is accounted for through the lens of the wealthy and those in power. Classical art is a reflection only of the history as seen through the oppressors, not the oppressed.

At the same time, it’s clear that there is merit to classical art. I shouldn’t completely reject it and speak of it as it were an evil. There is credit due to the skill and ability of the artists in developing distinctive artistic styles and making gains in artistic innovation. The problem comes with the name lent to subcategory of “classical art.” By labeling it as so, we’re perpetuating this vision that classical art (aka unrepresentative art) is the ideal. But it’s not. And it’s time we start saying so.