I traced my finger over his name a few times. Sampson.

I was sitting in the low light of the Historical Society of Philadelphia archives, struggling to read the curly colonial handwriting. It was here I found the name “Sampson” on Thomas Cadwalader’s will. Cadwalader was an early University of Pennsylvania trustee, whose wealth and leadership helped establish the university. The will revealed that the Cadwalader family was passing Sampson down along with plots of land, sums of money, and the family jewels. Sampson wouldn’t have been able to read the document that passed him to a Cadwalader heir. He was listed on it as though he were a piece of property.

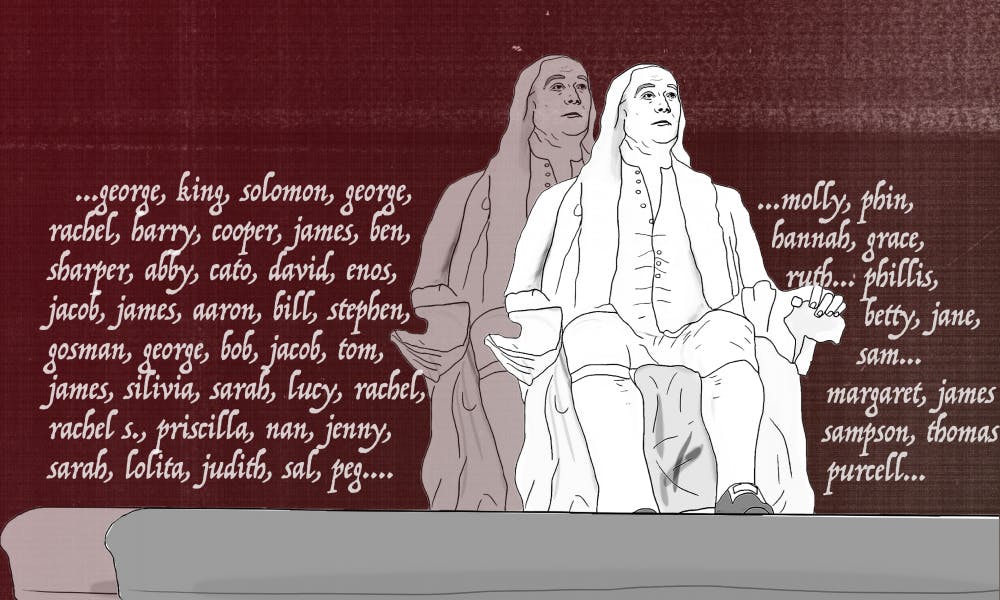

And although I haven’t been able to find out much more about Sampson, I do have his name. I have a lot of names. I have a list of 51 names of slaves owned by early Penn trustees:

Note: the list of slaves is not yet complete. Many enslaved people were only listed as “negro boy” or “negro wench.”

Some of these enslaved people escaped to freedom. Some were granted freedom after their masters died. Some died in servitude. These names were listed in wills, letters, and ledgers that were unearthed by the Penn History of Slavery Project—a joint research effort between Penn undergraduates and Penn History professor Kathleen Brown.

As an English major, I stumbled into the project quite accidentally. In the spring of 2017, I took Professor Brown’s history class, HIST 011: Deciphering America, which was co–taught by Professor Walter Licht.

Author VanJessica Gladney, one of the students who helped spearhead research into Penn's ties to slavery

I talked with both professors on the way out of class and asked their opinion on Yale’s decision to rename the residential college named for Yale alum and slavery advocate John C. Calhoun. Professor Brown put it simply: academic institutions have a responsibility to take an honest look at their past. Her answer struck a chord with me. She mentioned her plans to put together a research group to look at Penn’s own history with slavery. I told her that, even though I wasn’t a History major, I would love to be part of the team.

The group met during reading days a few months later in Professor Brown’s office. We didn’t know each other when we took Professor Brown’s history class, and most of us found out about the project afterwards. I’m one of five undergraduates in the group, along with Caitlin Doolittle (C ’18), Dillon Kersh (C ‘20), Matthew Palczynski (C ‘17), and Brooke Krancer (C ‘20), who is also the social media director for The Daily Pennsylvanian.

Though the project was still far on the horizon, Professor Brown made one thing clear early on: this was our project. We were not lowly undergrads doing grunt work for a professor’s research project. We were in charge of looking for our information and documenting what we found. The meetings were to take place every other Friday morning. We would bring our information and findings. She would bring advice, guidance, and doughnuts. She gave us the list of books and articles to read over the summer, then sent us on our way.

Although we arrived at the project in different ways, each of us had the common desire to reveal an obscured truth.

“Penn's version of history has long been whitewashed, after all, and it is high time we recognized that,” my teammate Matthew explained.

Last semester we focused on the trustees who worked as merchants connected to the slave trade, as they were the most likely to have owned slaves themselves. These public records showed that men paid taxes on their property: horses, carriages, land, and slaves. Once we knew who owned slaves, we wanted to learn as much as possible about the slaves themselves. We took the list of trustees to the University Archives and the Historical Society of Philadelphia. There, we looked through wills, letters, and other documents to try and put names to the numbers we’d found on the tax records.

Over the semester, I learned a lot about the trustees who owned slaves.

The early trustees of the University of Pennsylvania helped design symbols of American freedom while keeping other men in bondage. According to notes from the Continental Congress, Francis Hopkinson, an early trustee and slave owner, designed America’s very first flag. Isaac Norris Jr., another trustee and slave owner, chose the inscription for the bell, now known as the “Liberty Bell,” that hung in the Pennsylvania State House:

“Proclaim liberty throughout all the land and unto all the inhabitants thereof.” —Leviticus 25:10

Seven of the early trustees of the University of Pennsylvania signed the Declaration of Independence, eight signed the United States Constitution, and four signed both: George Clymer, Robert Morris, James Wilson, and Benjamin Franklin. Though Clymer’s record has not been searched, we know that the last three men owned slaves. They signed a document declaring all men equal, and owned men they deemed unworthy of those same rights.

The University’s ties to the slave trade run further than the trustees. William Smith was the first provost of the University of Pennsylvania. He taught ethics at Penn and exchanged letters with George Washington and Thomas Jefferson. Tax records suggest that he owned a slave while he served as our provost.

I was happy our team was finding names of enslaved people, but I was angry that there were so many. And I was even angrier that there are some names we might never find. I understood that these men gained their wealth by taking it from others, but their wealth funded and founded a university I am very proud to attend.

After I began the project, I spoke to a roommate to try and untangle the feelings of satisfaction and pain from my work in the archives. Each discovery was heartbreaking and infuriating and uplifting and empowering, all at once.

While I was speaking, one of my roommate’s friends interrupted and asked me if I was doing this research “just to make Penn look bad.” The question hung in the air until my friend changed the subject. And I’m glad she did, because I needed some time to think about how to phrase my response.

Since that conversation, I’ve had ample opportunities to talk about the research. We delivered three presentations: two on campus in mid–December last fall, and a third at the Museum of the Revolution in January. During one presentation, while my teammates were naming slave owners and listing numbers of enslaved people, I remember seeing expressions of surprise and shock in the audience. I was mildly confused why everyone was so surprised about this research.

I made eye contact with another person of color across the room, and his expression matched my feelings exactly: this was something I thought everyone already knew.

Members of the Penn History of Slavery Project team (left to right): Carson Eckhard, Caitlin Doolittle, VanJessica Gladney, Brooke Krancer, Dillon Kersh

I’ve found that discussions of Penn’s involvement in the institution of slavery focus on its reputation. During presentations of our research, a comment or question from the audience would twist the conversation away from Penn and turn it towards another university: Georgetown. Georgetown’s involvement in the slave trade is well known because of the staggering number of slaves sold. I remember hearing the phrase “This is not a Georgetown situation.”

Yes, it’s true—the University of Pennsylvania has a different history than Georgetown University and Philadelphia has a different history than other cities. But that isn’t related to the people enslaved in either place. I have yet to find an account where a slave considered themselves lucky because they weren’t working at Georgetown.

This research is not supposed to start a competition to see which institution has the fewest ties to the American slave trade. This is not an attack on Penn’s reputation. This is a search for the truth. The desire for reassurance that one institution’s history is less problematic than another speaks to a reluctance to engage in a genuine discussion about slavery.

This attitude was evident in that the statement the University issued commending our team’s research, signed by President Amy Gutmann and Provost Wendell Pritchett. In part, it said:

“While it has long been known that Penn’s founder, Benjamin Franklin had owned slaves early in his life before becoming a leading abolitionist, the students’ work cast a new light on our historical understanding of the reach of slavery’s connections to Penn.”

Although we appreciated the recognition, the rest of the statement included details about the slave owners that were either missing or incorrect. We were not able to conduct thorough research on all of the trustees, so we cannot yet be certain that “approximately half of Penn’s early Trustees owned slaves,” as the statement claimed. Of the 126 early trustees, we have only investigated 28, and found that 20 of them owned slaves. It also neglected to mention a previous statement made by the University in 2016, published in the Philadelphia Tribune: “Penn has explored this issue several times over the past few decades and found no direct university involvement with slavery or the slave trade.” Or the fact that, in 2006, the University claimed no ties to slavery while universities like Brown and Harvard were devoting resources to the question of historical legacy.

“Our university was indeed complicit in slavery. If we want to be the institution we claim to be, we must acknowledge all aspects of Penn’s complicated legacy and proceed accordingly,” Carson Eckhard (C ‘21), a new member of the project, noted.

While the most recent statement and the one in 2016 do mention that Penn’s most famous founder, Benjamin Franklin owned slaves, both immediately defend his reputation by emphasizing his involvement in the abolition movement. Mentioning both in the same breath says a lot about the way America chooses to understand slavery. It shifts the conversation from the enslaved people and back to the men who enslaved them.

This country was built by slaves. The economy and manufacturing relied on that free labor. Slavery is a huge piece of America’s foundation. It is impossible to disentangle slavery from the country’s history, and impossible to miss how it affects the country to this day. When the founding fathers drafted the Declaration of Independence and the US Constitution, they spent hours discussing how to protect and preserve the institution without actually writing the word “slave.”

It requires a great deal of wealth to found and fund a university. And it is not all that surprising that the colonial wealth that paid for our University was a direct result of the slave trade. For me, “Was Penn involved in slavery?” is an easy question to answer. Everything founded during America’s colonial period has ties to slavery.

In a February 26 email to Street, Provost Wendell Pritchett stated that he is “chairing a small working group that will incorporate the students’ research and solicit their input, along with advice from other members of our community, and then make recommendations to President Gutmann before the end of the semester.”

The research conducted by the Penn Slavery Project has given the University an opportunity to further its exploration of its own history. Penn has the opportunity to learn names that were forcibly erased. Penn has the opportunity to connect bloodlines that were deliberately broken. And the opportunity to include stories that, to this day, remain ignored. We would be remiss not to take advantage of it.

VanJessica Gladney is a senior from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. She is studying English.

The author would like to thank her fellow teammates, Professor Brown, and Mr. Mark Lloyd, without whom, these names would remain forgotten; the University administration, who has stated their support of these academic efforts; and the student–run publications who have been actively involved in continuing this conversation.