It’s Friday, November 11 at 4:30 pm. I wrap up my weekly seminar at Perry World House and stand in the conference room along with few other students chatting. As her face turns red, a student asks, “Have you seen the racist GroupMe on Facebook?” I respond, “No, I haven’t yet.” She appears to hold her tears back. “It’s disgusting with images of lynchings, and it’s all over Facebook.” We stand quiet for a moment, scared, confused, and realizing that Penn cannot shield us from the venom of those who wish to hurt us. We are black, white, Middle Eastern. We are overwhelmed.

That Friday, six Penn freshmen were added into a GroupMe chat titled “Trump is Love.” The chat was rife with racist content, including a calendar event titled “daily lynching,” messages like “Never be a N----r in SAE,” and a graphic photograph of a lynching.

Screenshots of the GroupMe quickly circulated amongst students through Facebook. Calvary Rogers (C’19), who is the co–chair of UMOJA and also works as a DP columnist, found out in real time about the GroupMe account through a student who was added into it. “I never thought something like this would happen at Penn,” he said.

Around noon, the Division of Public Safety became aware of the messages. Vice President for Public Safety Maureen Rush later said that there was no evidence that Penn was targeted specifically for being Trump’s alma mater.

By early Friday evening, Penn President Amy Gutmann sent an email to the student body, acknowledging the event: “We are absolutely appalled that earlier today Black freshman students at Penn were added to a racist GroupMe account that appears to be based in Oklahoma,” the statement read. “The account itself is totally repugnant: it contains violent, racist and thoroughly disgusting images and messages.”

DPS would later work into the night with black student leaders, trying to identify those freshmen who were added into the chat, as well as coordinating interviews with the FBI.

Early the next day, the University announced that a student at the University of Oklahoma had been suspended due to his suspected role in sending the messages. Two other students have also been investigated by the FBI in connection with the GroupMe chat. All of the students attended the same high school, Rush said. One was a Penn admit to the class of 2020—he was able to gather Penn students’ names and add them to the GroupMe chat through the official Class of 2020 Facebook Page, which he was still a part of.

Penn’s Chaplain Rev. Charles L. Howard works closely with Student Intervention Services and public safety on a range of crises and was among the University’s administrators who handled the GroupMe incident.

“We all did what we could, whether it was pulling together the students who were threatened, getting food or talking to students one–on–one throughout the day and being at the gatherings to say a quick word of encouragement,” Howard said.

Now, four months later, the FBI investigation is still ongoing and no students have been charged.

Aftermath

Howard noted the incident reverberated well beyond the black community. “The entire school was devastated, let alone several hundred black students,” Howard said.

“As a black administrator here, my biggest hurt is the pain that I have seen it cause my students, and to see my students crying really hurts my heart,” he said.

For Calvary, the GroupMe incident took an emotional, psychological and physical toll on him. Though Howard said the administration notified the professors and counselors of the six students who were added to the chat, other students struggled with their academics in the wake of the event.

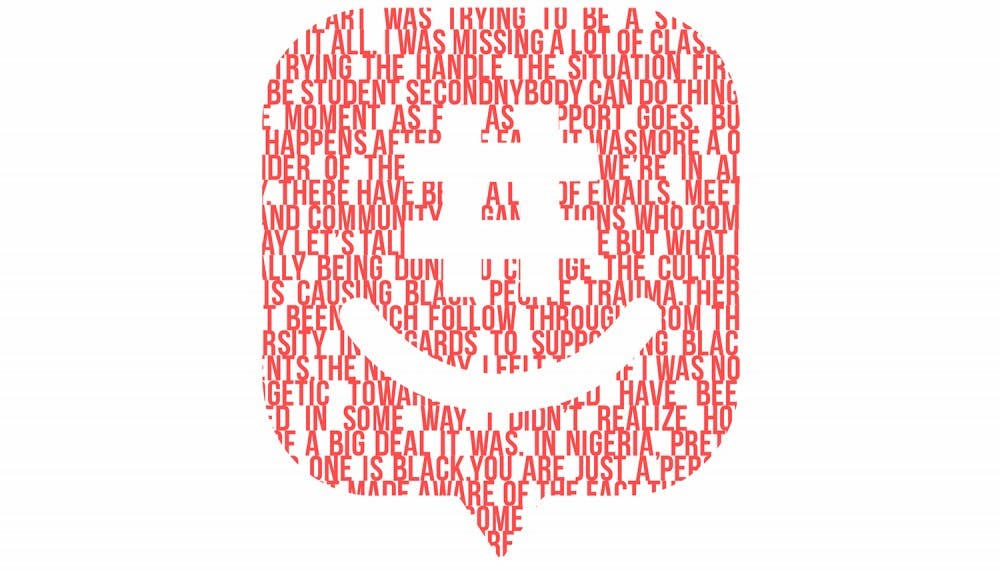

“The hardest part was trying to be a student through it all,” Calvary said. “I was missing a lot of classes. I was trying to handle the situation first and be a student second.”

Aisha Bowen, a first–year graduate student at Penn’s Graduate School of Education, also had problems focusing as she coped with the GroupMe incident and the way the school addressed the situation.

“What concerns me the most with this follow through is anybody can do things in the moment as far as support goes. But what happens after the fact?” she asked.

Kassidi Jones (C’18) thought being surprised by the event would be naive considering the results of the election and the current tense atmosphere in the country.

“[The incident] wasn’t really shocking but more of a reminder of the climate that we’re in already,” Kassidi said. She emphasized that it would be impossible for Penn to “protect us from things that are going on in the outside world.”

From Aisha’s perspective, most of what the administration did was send out emails to students, explaining moment by moment the developments of the GroupMe incident. “The administration kept the students informed rather than saying we are here for you,” she recalled.

Miebaka Anga (C’18) recognized similar flaws. Instead of providing support, he wished the school took more preventative measures rather than offer reactionary support. Aisha agreed, questioning the actions Penn has taken since the incident occurred.

“What actual tangible changes have happened?” Aisha asked. “There have been a lot of emails, meetings and community organizations who come and say let’s talk and let’s share, but what is actually being done to change the culture that is causing black people trauma?”

Kassidi said that Penn has more work to do, but she feels supported by the people around her, such as individuals in the Africana Studies department and Makuu, the black cultural center on campus.

Though many students who were added into the GroupMe did not respond to requests for comment, a few of them told Aisha that there “hasn’t been much follow through from the University in regards to supporting black students.”

Figures in the administration like Howard are sympathetic to these complaints. “I can see the frustration with the lack of follow up with the entire black community, and that’s a good check on us,” he said. “We should have another large gathering. We can all come together to follow up as a community.”

Racism at Penn

One night, Miebaka was at a party off–campus with other Penn students when he says police officers told them to leave. He was standing outside along with a white friend, waiting for the rest of their group to come out. One of the officers asked what they were still doing there and allowed his white friend to go. Meanwhile, he continued to ask Miebaka questions and shouted at him. Miebaka remained calm and apologized to the officer multiple times.

“The next day, I felt that if I was not apologetic toward him,” he explained, “I could have been harmed in some way. That may feel like a big assumption, but that’s how I felt reflecting back on it.”

His father had warned him about the prevalence of racism in the U.S. before he came to Penn from Nigeria—warnings that Miebaka initially didn’t fully understand. “I didn’t read into it much,” he said, “and almost approached it with the mindset of what is he talking about?”

Miebaka is still coming to terms with the concept of racism. “I didn’t realize how much of a big deal it was,” he said.

In Nigeria, “pretty much no one is black,” he said. “You are just a person; you are not made aware of the fact that you are black until you come here. Then, it’s a thing.”

Aisha said she has endured both overt and covert racism on campus. She has been, for instance, mistaken at the University as a student who doesn’t attend the school.

She noted that “the racist culture and this type of aura is not something that’s new on campus for a lot of these black students because we experience it ourselves.” Just three years ago, for example, the Phi Delta Theta fraternity received backlash for taking a Christmas photo of mainly white males that included a black blow–up doll. In 1993, Penn was similarly wracked by a racial scandal when a white freshman called out to a group of black women to “shut up, you water buffalo.” These are more than mere isolated incidents—they are part of the often daily struggles that black students and faculty alike are forced to confront. Howard was called the N–word to his face as a high schooler, and to this day, when he writes articles, he often hears the same racist language in emails and phone calls.

“I didn’t have the same surprise that I do think some other people felt about this still happening in 2016,” he said, “but I did feel the sting of it still.”

In the aftermath of the GroupMe messages, protesters marched in solidarity to the evening football game at Franklin Field. Aisha recalled that many white students did not welcome their black peers’ outrage. “The response that a lot of students gave to the marchers was ‘I don’t understand why they are acting this way. You guys need to be more calm,'” she said. “That is telling black students you are not allowed to respond with the emotions of a human being.”

For Kassidi, the racism she has experienced has been more subtle. Some of her Penn classmates have complimented her for being “articulate,” even though she already attends an Ivy League university.

“Some are surprised by the fact that I know how to talk well,” Kassidi said. “It should be expected that I am on the same level of intellect that my peers are.”

Calvary has also experienced numerous hidden forms of racism on campus. Many Penn staff members have assumed that he is an athlete because he is black, often singling him out while he’s with his white peers to ask what sport he plays. Once, as he passed by a group of high school students with their Penn tour guide, a white parent asked the guide whether "blacks" are allowed on campus.

“There were times that I thought people didn’t want me here,” he said. The people who sent those messages “literally wanted to lynch me, but I reminded myself of the bigger picture.”

“No matter how far I go, what school I get into, what job I take, I am always going to be subjected to this racism that doesn't even see me as a person,” Calvary said.

Part of that racial climate at Penn stems from demographics. As of fall 2015, among the Penn undergraduates only 7 percent were black Americans while 44.3 percent were white. For graduate students, just 5 percent were black Americans while 45.6 percent were white. Black faculty were even more underrepresented; only 3.8 percent black, compared to 76.6 percent white.

In a recent talk at the World Cafe Live, Marybeth Gasman, a professor at Penn’s Graduate School of Education, pointed out that “not hiring as many faculty of color is just as bad. People have a hard time understanding how bad systemic racism is.”

Vice Provost for Faculty Anita Allen wrote in an email to Street saying that “Penn diligently seeks to always abide by legally prescribed affirmative action / equal opportunity policies. I am proud that women and people of color contribute to our inclusive and increasingly diverse campus. Faculty diversity and inclusion are stated priorities of the university.”

Gasman noted that for the white community, the whole Penn campus is their space. These spaces were built for white men, and still exhibit their sculptures and portraits to this day. Aisha shared a similar thought. “That’s a privilege that a lot of white students on this campus have,” she said. “The people that they read about, the books that they read are people that come from a culture that they ascribe to. And when they do learn about themselves, for the most part, it’s very positive.”

Working to Change

Over his 21 years at the school, even with the enduring grip of racism both open and hidden at the University, Howard has witnessed progress on the issue.

“We are not there yet; we are nowhere near the promised land, but we are a whole lot better than when I was a freshman,” Howard said. “Again, kids are still being called the N–word. There are still racist parties. That’s not okay. We are still working on it, and we have to keep working on it and not be comfortable where we are.”

While people are hoping for progress in the University, many have also expressed disappointment in the aftermath of Trump’s election. Though many Americans have spoken of leaving the country, Kassidi has no intention of leaving.

“I don’t want to uproot myself to make white supremacy feel more comfortable in America,” she explained. “I’d rather stay in the place that I know, fight the same demons that I know.”

Gasman pointed out that white people need to be just as engaged participants in the struggle against racism. “The best way to be a good ally,” she said, “is to listen, to believe people, to confront people who might be perpetuating these things in society. Because as white people, we need to do that.”

She added, “We need to acknowledge that for many many people, Trump’s election equated to a kind of comment about their value in society.”

Aisha echoed Gasman’s sentiments and encouraged people to work against the message that Trump’s election conveyed.

“A lot of black students on campus, specifically black freshman, are looking for support,” Aisha said. “They are looking for people to show them that their lives and their experiences are just as important as anyone else’s and that fact is shown through action.”

She added, “This place needs to have black students who will fight and who will come together to make change happen.”

Even if Penn makes improvements, Kassidi is cognizant of the fact that Penn is not a bubble and will always be subject to the racial context nationwide.

“We are not an isolated island where we can all be inclusive and open,” Kassidi said. “We are not an exception.”